|

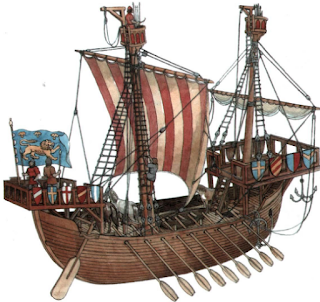

From the cover of Jewish Education and Society in the High Middle Ages, by Ephraim Kanarfogel.

|

INTRODUCTION:

I recall vividly, as a youngster just out of school and

about to study in yeshiva, how it was made very clear by my rabbis that

as bochurim (yeshiva students) we had to get, not just away from

our families, not just out of town, but out of the country in order to immerse

ourselves in study. Many children were sent overseas even earlier, as thirteen

and fourteen-year-olds, just after barmitzvah. I know some who never saw

their parents, brothers and sisters again, for years.

One of the yeshivot

I attended in Israel was great fun but rather ascetic in that we were given a certain elitist designation, not

allowed mirrors in the washrooms, and hardly allowed out on Shabbat, not even

to go to other yeshivot, never mind visiting family. If one chose,

instead, to study in a yeshiva in one’s hometown, no matter how good it

was, one lost a perceived status that was difficult to regain.

Where did these unwritten laws and perceptions come from?

Certainly, they have become part of the cultural authority of various modern

groups and sects, but their roots may have had their origins in earlier times.

This article, based extensively on the research of Rabbi

Professor Ephraim Kanarfogel

of Yeshiva University, deals with guidelines for early yeshiva schools

going back perhaps to the eleventh and twelfth centuries, and is based on the work Sefer

Chukei haTorah.

SEFER CHUKEI HATORAH:

There is only one extant version of Sefer Chukei haTorah and

it has three sections. The text is found in the Bodleian Library.

It reads like a manual or guideline for a strict pietist school system.

It’s an interesting work as it has many unknowns. For some

reason, it is not cited by later rabbinic literature although two later texts

are fairly similar to it.

Sefer Chukei haTorah was eventually only published in

1880, by Moritz Guedermann. Since then, over twenty-five scholars have argued

and debated over its date of origin and general provenance. The work makes

mention of Gaonim (rabbis from the Gaonic period 589-1038) and some believe it

may have been written during that time.

On the other hand, it shows resemblance

to the midrash hagadol or great academy which was prevalent in southern France in the twelfth century.

The historian Salo Baron (1895-1989) writes that Sefer

Chukei haTorah originated:

“...in one of the northern

communities under the impact of Provençal

mysticism or of German-Jewish Pietism [i.e., the mystical movement known as

Chassidei Ashkenaz]

of the school of Yehudah the Pious and Eleazar of Worms.”

This indicates that Sefer Chukei haTorah had intense

mystical origins.

a) PROGRESSIVE TEACHINGS:

Rabbi Professor Isadore Twersky (1930-1997) sums up the

essence of Sefer Chukei haTorah as

being most progressive:

“It strives, by way of

stipulations and suggestions, to achieve maximum learning on the part of the

student and maximum dedication on the part of the teacher. It operates with

such progressive notions as determining the occupational aptitude of students,

arranging small groups in order to enable individual attention, grading the

classes in order not to stifle individual progress.

The teacher is urged to

encourage free debate and discussion among students, arrange periodic

review...utilize the vernacular in order to facilitate comprehension. Above

all, he is warned against insincerity and is exhorted to be wholly committed to

his noble profession.”

Sefer Chukei haTorah also stresses that teachers be

completely committed to their teaching while in class and not allow anything to

distract them. Even the Dean may not interrupt the teacher while he is engaged

in his work with the students.

These are, as R. Twersky describes, very progressive

pedagogic measures particularly for a school system some eight centuries ago.

b) ASCETIC AND PIETISTIC TEACHINGS:

However, one can argue that Sefer Chukei haTorah also

encouraged strict ascetic practices as well. It tells how the sons of the Cohanim and Leviyim were ‘consecrated’ and expected to study in these schools full time, although this was not enforced. Designated scholars would also study full time – and, importantly, the communal responsibility to study Torah was considered to be vicariously discharged through these students. The students are not just called students, but perushim, or separatists who have been ‘consecrated’

to distance themselves from not just the outside world, but even from their own

families.

Kanarfogel writes:

“The most novel position of

this document calls for the establishment of quasi-monastic study halls for perushim

(lit., those who are separate), dedicated students who would remain totally

immersed in their Torah studies for a period of seven years. Elementary-level

students would be taught in separate structures for a period of up to seven

years, in preparation for their initiation into the ranks of the perushim.

The formal initiation took place when the student was thirteen, although it

could be postponed (or perhaps renounced) until age sixteen.”

This makes a total of fourteen years of study within these institutions.

The fact that Kanarfogal, who is most articulate in his use

of words, refers to ‘quasi-monastic study halls for perushim’ is

significant because he suggests a possible non-Jewish ascetic influence.

Elsewhere, Kanarfogel writes about the Tosafist’s (also active

during the same period - around the twelfth and thirteenth centuries) whose analytical

style of dialectics is referred to by the Sefer Chassidim as ‘dialectica

shel goyim’ or dialectics of the non-Jews. He shows how the

signature analytical style of the Tosafists may have been adopted by Jews influenced

by the culture of dialectics popular in Christian France.

Rabbi Professor Yaakov Elman shows many earlier examples of influences from the surrounding outside culture which were prevalent during the times of the

Babylonian Talmud. A significant example is that of Jewish women who opted for stricter

observances when it came to the laws of family purity, so as not to be spiritually upstaged

by their more ascetic Zoroastrian neighbours.

If Kanarfogel is correct, it is possible that both the

dialectic style of the Tosafists and the ascetic approach to education that we

see in Sefer Chukei haTorah, may both have been influenced by the

prevailing religious milieu as found within cathedral and monastic schools in

Europe at that time.

Sefer Chukei haTorah discourages the classes taking

place in the house of the academy head lest he is distracted by his wife. The

classes must take place in the school of the perushim (the students who

have separated). The academy head must remain with the students and not return

home for the entire week. He may only return home for Shabbat.

SEFER CHUKEI HATORAH RESEMBLES SEFER CHASSIDIM:

Sefer Chukei haTorah reflects many ideas that are

mentioned in Sefer Chassidim of the German Pietists (Chassidei

Ashkenaz).

Sefer Chassidim also expects the children of Cohanim

and Leviyim to be sent away from home for long periods of time, in order

to study Torah, or until they no longer have doubts. This is based on its unusual

interpretation of a verse in Devarim recording Moshe’s blessing before he died:

“Who said of his father and

mother, “I consider them not.” His brothers he disregarded, ignored his own

children. Your precepts alone they observed and kept your covenant.”

Kanarfogel says that he knows of no other text that

interprets this verse the way Sefer Chassidim does, other than what

appears to be its sister work, Sefer Chukei haTorah.

He writes:

“...the sons of kohanim and

leviyyim are to be consecrated as youngsters to study Torah and to become

perushim [separatists].

They are to remain separated from everyone including their families for seven

years, while they study.”

Thus Sefer Chukei haTorah seems to follow a similar educational

approach to that of Sefer Chassidim.

MONASTIC INFLUENCES?

Based on this and other similarities

between Sefer Chukei haTorah and Sefer Chassidim, it is possible that

the pietistic teachings of the former were influenced by the latter.

However, Kanarfogel suggests that some influences may also

have been absorbed from the surrounding religious culture of Christian piety

which was reflected in its educational system.

He writes:

“Another possible key to the

origin of [Sefer Chukei haTorah] that has not been probed sufficiently lies in

the practices and phrases that appear to be similar to Christian monastic

ideals. The perushim, who are chosen originally through some form of parental

consecration, ensconce themselves in their fortresses of study away from all

worldly temptations.

They devote all their time in

the holy work of God (melekhet shamayim), and serve as representatives of the

rest of the community in this endeavour. It is possible that the [Sefer Chukei

haTorah] represents an attempt to recast the discipline and devotion of

Christian monastic education, which was certainly known to, and perhaps admired

by, Jews, in a form compatible with Jewish practices and values.”

EXTRACTS FROM THE TEXT

OF SEFER CHUKEI HATORAH:

The following are some selected

extracts from Sefer Chukei haTorah:

1) NUMBERS OF STUDENTS IN A CLASS:

“Statute six. Melammedim

[teachers]

should not accept more than ten students in one class...”.

2) TO TEACH FROM A TEXT:

“Statute seven. It is

incumbent upon the melammedim not to teach the children by heart, but

from the written text....”

3) NOT TO LINGER IN THE SYNAGOGUE:

The heads of the academies

should not linger in the synagogue for morning prayer until the prayer

[service] ends, but only until...qedushah rabbah...”

4) THE RECULCITRANT STUDENT:

“Statute five.....And if the

supervisor sees amongst the youths a young man who is difficult and dense, he

should bring him to his father and say to him: ‘The Lord should privilege your

son to [do] good deeds, because he is too difficult for Torah study,’ lest the

brighter students fall behind because of him.”

5) FINANCIAL MATTERS:

"Statute four. To collect from all Israel twelve deniers a year for the service of the study hall....”

“And it was ordained regarding

the melammedim, that a head melamed can gather up to one hundred

young men to teach them Torah, and take in for this one hundred litrin.

He then hires for them ten melammedim for eighty litrin, and the

remaining litrin will be his share. He does not teach any child but is

the officer and supervisor over the [other] melammedim....”

“[The father of a five year

old]

informs the melammed...’I am telling you that you will teach my son

during this month the structure of the letters, during the second month their

vocalization, during the third month the combination of letters into

words....If not, you will be paid as a furloughed [temporary]worker.’”

6) CONSECRATION WHILE IN THE WOMB:

“The first statute. It is

incumbent on the priests and Levites to separate one of their sons and consecrate

him to Torah study, even while he is still in his mother’s womb. For they were

commanded this at Mount Sinai as it is written, “they shall teach your statutes

to Jacob. [Deut.33:10]....”

“[The father] accepts upon

himself and says: ‘If my wife gives birth to a male, he shall be consecrated

unto the Lord, and he will study His Torah day and night.’ On the eighth day,

after the child has entered the covenant of circumcision....[t]he academy head

shall place his hands on him and on the Pentateuch and say, ‘this one shall

learn what is written in this,’ three times....”

7) THE ‘TITHE OF SONS’:

“Similarly, all the children

of Israel shall separate [one] from among their sons, because Jacob made such a

separation, as it is written, “all that You shall give to me I will surely give

the tenth [double verb] to You” [Gen. 28:22]. The verse speaks of two tithings,

a tithe of money and a tithe of sons....”

8) THE FEW STUDY FOR THE MANY:

“Statute two. To establish a

study hall for the separated students [perushim]...near the synagogue.

This house would be called the great study hall.

For just as cantors are

appointed to discharge for the many their obligation in prayer, full-time

students are appointed to study Torah without end, to discharge for the many

their obligation in Torah study, and the work of heaven will thereby not fall

behind....”

9) THE STUDENTS MAY NOT LEAVE FOR SEVEN YEARS:

“Statute three. The perushim

may not leave the house for seven years. There they will eat and drink, and

there they will sleep, and they should not speak in the study hall.

Wisdom will not reside in the

student who comes and goes...

If the perushim leave

the study hall before seven years, they must pay a set fine...which teaches

that they imprison themselves in order to know the statutes of the Almighty....”

ANALYSIS:

The first five extracts

are indeed quite ‘progressive’ as per R. Twersky - but the last four appear extremely

ascetic and do seem to reflect a monastic approach as per R. Kanarfogel, making

his hypothesis rather convincing.

FURTHER READING:

Jewish Education and Society in the High Middle Ages, by Ephraim Kanarfogel. Detroit. Wayne State University Press.

Michal Bar-Asher Siegal. Shared Worlds: Rabbinic and Monastic

Literature. Ben Gurion University.

[1] Ephraim Kanarfogel, A Monastic-like Setting for the

Study of Torah: Sefer Huqqei ha-Torah.

[2] Opp. 342, fols. 196-199 (Neubauer 873).

[5] Isadore Twersky, Rabad of Posquiéres, 2nd ed.

(Philidelphia: Jewish Publication Society 1980, p. 25.

[6] Deuteronomy 33:9. It is interesting to note that the next

verse, verse 10 reads: “They

shall teach Your ordinances to Jacob, and Your Torah to

Israel” and verse 11 reads: “May the Lord bless his army”. It is

possible that this interpretation of Sefer Chassidim may be

the originator of the notion that the students of Torah represent the mystical army that

protects the Jewish people. (Interpretation mine.)

[8] Kanarfogel adds that similar sentiments were also expressed in

the Sefer Chassidim of Chassidei Ashkenaz, that

students of different levels should not be included together in one combined

class as both the bright and the weaker students would suffer.