|

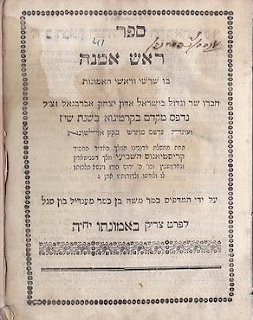

| A 1767 edition of Abravanel's Mashmia Yeshua. |

INTROUCTION:

The Portuguese statesman and

commentator R. Don Yitzchak Abravanel (1437-1508) had lived through the harsh

period of the Expulsion of practicing Jews from Spain and Portugal in 1492 and

1497 respectively. He sought to inspire his people by encouraging messianic

hope in order to counter the general feelings of hopelessness and despair.

Between 1496 and 1498 he wrote three messianic works: מעייני הישועה, "The Wellsprings of Salvation", a

commentary on the Book of Daniel; ישועות משיחו,

"The Salvation of His Anointed", an interpretation of rabbinic

literature about the Messiah; משמיע

ישועה,

"Announcing Salvation", a commentary on the messianic

prophecies in the prophetical books. These form part of the larger work

entitled מגדל

ישועות,

"Tower of Salvation". Abravanel counts Daniel - a symbol of

the messianic idea - as one of the prophets, which goes against the Talmudic

and rabbinic tradition which places the book under Ketuvin (Writings)

and not Nevi’im (Prophets).

This article, based extensively

on the research by Professor Eric Lawee

deals with some of these messianic ideas expressed by the so-called ‘father’ of

Jewish messianic movements, Abravanel. After the Expulsion, Abravanel believed

that the messianic arrival was imminent. Most of Abravanel’s messianic writings

took place in the post-Expulsion period.

Generally speaking, scholars have

held that Abravanel’s messianism was influential in shaping future messianic

trends within Judaism, but as we shall see, Lawee points out that that assumption

is not always so clear.