|

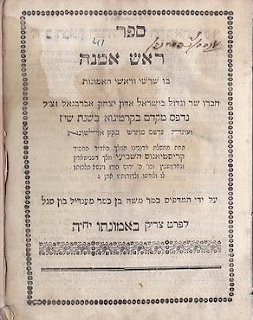

| Shem haGedolim by R. Chaim David Azulai, known as the Chida (1724-1806). |

Introduction

This article—based extensively on the research by Dr Oded Cohen[1]—examines the challenges facing editors of religious Jewish texts. It deals with two very different editors and separated by six hundred years, yet who faced similar tasks and scrutiny.

The first editor is the Maskil of the Enlightenment movement, Isaac Benjacob (1801-1863), who edited the Shem haGedolim of the R. Chaim David Azulai, known as the Chida (1724-1806).

The second is Maimonides, who—though not an editor of the Babylonian Talmud in the conventional sense—systematically distilled its legal rulings into his Mishneh Torah, the ground-breaking code that stripped away dialectical debate in favour of a clear, authoritative Halachic structure.

%20and%204%20more%20pages%20-%20Profile%201%20-%20Mi.png)