|

| Likkutim with references to Sefer haIyun and Shem Tov Ibn Gaon (see Appendix): |

- POLEMICS OF AN EARLY MYSTICAL POWER-STRUGGLE -

INTRODUCTION:

The Zohar was first published (in manuscript form) in around

1280. During that century and the next, there was much debate over who wrote

it, who owned it and - more importantly - who owned the Kabbalistic

tradition in general.

The publication of the Zohar brought the issue of

ownership of Kabbalah to a head because this was the beginning of a new literary

(written) mystical tradition replacing a hitherto largely oral mystical

tradition.

In this article, we will explore the question of who owned

the authentic rights to Kabbalah. Was it those who wrote, read and studied its books - or those who transmitted

and expounded it the form of an oral tradition?

I have drawn

extensively from Professor Moshe Halbertal,

a graduate of Har Etzion Yeshiva who later served, amongst other positions, as

visiting professor at Yale and Harvard Universities. He is also the co-author

of the Israeli Army Code of Ethics.

Considering the prime role the Zohar and Kabbalah were to play in future Judaism, it is interesting to see how ideas we usually take for granted as always being part of Jewish tradition, were fiercely debated at that time.

What is refreshing about this account is that it is not

historical speculation but, instead, a record of ‘eye witness’ writings of two

contemporaneous Kabbalists from each of the two competing mystical

schools at the time of the publication of the Zohar in the late 13th-

century. It is the story of the battle between the established older oral mystical tradition and the infancy and stirrings of a new competing written tradition.

THE CLASH OF THE LITERARY AND ORAL MYSTICAL TRADITIONS:

Moshe Halbertal presents the problem:

“The emergence of literary

canon endows a tradition with authority and endurance, which is independent

from the localized and bounded channels of oral transmission. Yet such

transformation might undermine that same tradition it aimed at solidifying.”

MEIR IBN SAHULA VS SHEM TOV IBN GAON:

This tension resulted in a clash between the newer literary

and older oral mystical traditions. The clash may be personified

as a conflict between two exponents of these traditions, namely Meir Ibn Sahula

(1255-1335) representing what was to become the new literary tradition, and

Shem Tov Ibn Gaon (1283-1330) representing the older oral tradition.

PART 1:

MEIR IBN SAHULA:

WRITTEN TEXTS AND MEIR IBN SAHULA’S INDEPENDENT MYSTICAL STUDY:

Towards the latter part of the 13th-century, the

Spanish Kabbalist Meir Ibn Sahula wrote about how he had acquired all

his mystical knowledge from books and not from an oral tradition. This was

something rather unusual at that time.

Meir Ibn Sahula had written a commentary to an earlier Kabbalistic

work, Sefer Yetzirah, and in it he writes:

"For several years

already, I have been studying these things relating to all secrets, starting

with the Sefer Habahir, which explains some matters, and the writings of Rabbi

Asher who wrote the Perush Shlosh Esreh Middot and the Perush Hashevu'ah, and

Rabbi Ezra , Rabbi Azariel and Rabbi Moshe ben Nahman [Nachmanides or Ramban],

all of blessed memory . Also, I studied those chapters. And I acquired some of

the commentary on Sefer Yetzirah attributed to Rabbi Moshe bar Nahman of

blessed memory, but I was unable to acquire all of it."

Evidently, Meir Ibn Sahula had access to a large body of

written mystical literature and he was happy to consult it and learn from it. However, he was the exception rather than the rule, as most Kabbalists

held to the very strict tradition of an oral mystical transmission. Mystical

books (baring one or two exceptions) and certainly libraries were considered

unauthentic and unauthorized for such an important tradition.

NACHMANIDES’ ORAL MYSTICAL TRADITION AND HIS OPPOSITION

TO INDEPENDENT MYSTICAL INQUIRY:

A strong advocate of the oral transmission of mystical

knowledge as the only way to study and understand these ideas was Nachmanides

(1194-1270). Nachmanides is generally known as the father of Jewish mysticism

and he promoted its transmission in a mostly oral form.

Nachmanides maintained that the mystical tradition was a

closed system which had its origins at Sinai and the only way to safeguard its

authenticity was, essentially, through oral transmission.

Nachmanides’ commonly adopted position can be seen in the Introduction

to his Commentary on the Torah:

"[C]oncerning any of the

mystic hints which I write regarding the hidden matters of the Torah...I do

hereby firmly make known to him [the reader] that my words will not be

comprehended nor known at all by any reasoning or contemplation, excepting from

the mouth of a wise Kabbalist speaking into the ear of an understanding recipient.

Reasoning about them is

foolishness; any unrelated thought brings much damage and withholds the

benefit... let them take moral instruction from the mouths of our holy

Rabbis...[A]bout that which is hidden from you, do not ask."

There was to be no innovation or space for any private

access to this knowledge. It could not be acquired independently. It had to be

given over only by the master who possessed and owned that knowledge.

MEIR IBN SAHULA AS INDEPENDENT MYSTICAL INQUIRER:

Accordingly, Meir Ibn Sahula can be considered a mystic rebel

in that he went against the dictates of mainstream Kabbalists and

promoted independent textual study of mystical literature.

Meir Ibn Sahula writes in stark contradistinction to

Nachmanides:

"We must investigate the

words according to our understanding, and walk in them in the paths walked by

the prophets in their generation and in the generations before us, during the

two hundred years of kabbalists to date, and they call the wisdom of the ten

sefirot and some of the reasons for the commandments[,] Kabbalah."

In another statement, Meir Ibn Sahula is even clearer:

"I did not receive this

from tradition, but I say 'open my eyes that I may gaze on the wonders of your

Law'."

Halbertal describes Meir Ibn Sahula as undermining the authority of the earlier Kabbalists:

“The restriction of the scope

of the tradition empowers the investigative position and his reliance on

reasoning.”

AGE AND PROVENANCE OF KABBALAH:

This “restriction of scope” is fundamentally

important because it now allows and admits the notion of innovation of mystical

ideas – something abhorrent to the mainstream Kabbalists like

Nachmanides who roots his mystical tradition in Sinai.

What is striking about the position taken by Meir Ibn Sahula

is that he sees much of Kabbalah as having developed later, especially

during the two hundred year period before him. This would be particularly significant

because new mystical ideas such as the Ten Sefirot

as defined by the more recent written works, were to become a cornerstone

and basic building block of much of future Jewish mysticism.

CHUG HAIYUN AND THEIR PSEUDEPIGRAPHA:

Besides the publication of the Zohar, there were numerous other mystical

writings - some more accurate than others - that were also in circulation. The

Spanish Kabbalists were particularly esoteric but one group from

Castille was even more extreme. They were known as the Chug haIyun or Circle

of In-Depth Contemplation. It is likely that Meir Ibn Sahula was part of this group.

They produced a vast mystical literature which was largely

pseudepigraphical (i.e., written falsely in the name of other, earlier and better

known authorities).

Halbertal refers to their pseudepigraphical enterprises as

“creative and daring.” They did not base their teachings on any oral

tradition. Instead, took their authority from (according to Halbertal a

mythical figure)

R. Chamai Gaon. They were intent on breaking the closed, secret and exclusive circle

of traditional Kabbalists like Nachmanides.

The writings of the Chug

haIyun - together with other mystical writings which accumulated from

various sectors of the Spanish mystical community - eventually culminated in

the writing of the Zohar, which further broke the notion that Kabbalah was

a closed system.

PART 2:

SHEM TOV IBN GAON:

SHEM TOV IBN GAON COMES TO THE DEFENCE OF NACHMANIDES:

At the other end of the spectrum - in light of the plethora

of newly published mystical literature - another mystic, Shem Tov Ibn Gaon

emerges as a defender of the more traditional system of oral transmission as

propounded by Nachmanides. He attempts to reinstate the closed model of Kabbalah

as an oral tradition only for the duly initiated.

Shem Tov Ibn Gaon was a student of Rashba (Rabbi Shlomo Ibn

Aderet - also known as the Rabbi of Spain - El Rab d'España) who in turn was a student

of Nachmanides.

Shem Tov Ibn Gaon writes about how, in his view, the oral

mystical tradition goes back to Sinai:

“For no sage can know of them

through his own sagacity, and no wise man may understand through his own

wisdom, and no researcher through his research, and no expositor through his

exposition; only the kabbalist may know, based on the Kabbalah that he

received, passed down orally from one man to another, going back to the chain

of the greats of the renowned generation, who received it from their masters,

and the fathers of their fathers, going back to Moses...who received it as Law

from Sinai.”

Shem Tov Ibn Gaon then takes a swipe at the style of popular

mystical writings that were beginning to emerge and he challenges their

authenticity:

"[E]very man whom the

spirit of God is within must take heed...lest he find books written with this

wisdom...for perhaps the whole of what he received is but chapter headings;

then he may come to study such books and fall in the deep pit as a result of

the sweet words he finds there; for he may rejoice in them, or desire their

secrets or the sweetness of the lofty language he finds there.

But perhaps their author has

not received the Kabbalah properly, passed down orally from one to another; he

may only have been intelligent or skilled in poetry or rhetoric... and have

left the true path, as our Sages of blessed memory warned, 'in the measure of

his sharpness, so is his error’.”

Probably because of the timing of Shem Tov Ibn Gaon’s writing so soon after the publication of the

Zohar, Halbertal interprets his word as follows:

“It may very well be that Shem

Τον Ibn Gaon was warning his readers against the Zohar, which is the epitome of

the development of the Kabbalah as literature, as its marvelous literary

qualities are powerfully seductive...

[The older and more

traditional oral mystical systems]

have no narrative frames or mythic characters, nor do they display complex

weaves of midrashim and explanations, whereas in the Zohar we find these

elements in abundance. The seductive appeal of the literary kabbalistic works

threaten its status as a precise tradition handed down by Moses on Mount Sinai;

it is this threat that Shem Tov struggled with.”

Halbertal points out that Nachmanides’ writings, in stark

contradistinction to the style of the Zohar, are ‘devoid of any literary

quality’. Nachmanides was not writing to entertain. Bear in mind that

Nachmanides would have passed away (in 1270) about ten years before the Zohar

was published (in 1280).

But Shem Tov Ibn Gaon hasn’t finished yet. Besides

criticising the abundance of new mystical literature, he launches into what

appears to be an attack against the Zohar seeming to accuse it of

pseudepigrapha. This is one of the first contemporaneous criticisms of the Zohar

which was to become the mainstay of Jewish mysticism:

"God forbid, for the

earlier instructed ones and the bearers of tradition have already proclaimed

against this, saying that the wise man should not read any book unless he knows

the name of its author.”

This statement needs to viewed against the backdrop of the fact

that although the Zohar was only published in 1280, it was claimed to have been

written by R. Shimon Bar Yochai, a Tanna from the Mishnaic Period one thousand

years earlier. It was claimed that some of Bar Yochai’s original manuscripts

had recently been found and only published in 1280 for the first time. Others

counterclaimed that the Zohar was a pseudepigraphic forgery written by Moshe de León (1240-1305).

Shem Tov Ibn Gaon continues:

“And this is just, for when he

knows whom its author is, he will understand its path and intention,

(transmitted) from one man to another until the members of his generation.

Thus, he may know if its author was a legitimate authority, and from whom he

received it and whether his wisdom is renowned."

Later, Shem Tov Ibn Gaon continues to highlight the

differences between his Nachmanidean school and the new and emerging literary Kabbalistic

tradition:

"[The traditional

mystical schools] were careful not to compose unattributed literature, writing

only in their own names. Furthermore, they never explained anything based on

their own knowledge, unless they made public to all readers how they arrived at

such knowledge through their own reasoning. They publicized their names in

their works so that all who come after them may know what guarded measure and

in which paths light may be found."

This was not the case with the new emerging written mystical

schools which thrived on grand pseudepigraphical enterprises.

SOME WRITTEN WORKS ARE CONSIDERED AS PART OF THE ORAL TRANSMISSION:

Shem Tov Ibn Gaon was now faced with a dilemma: He opposed

the emergence of the Zohar and other new writings because they were not part of

the oral mystical tradition, but there were some older literary works that

predated his era and he felt that they were authentic. These works included the

Sefer haBahir, Sefer Yetzirah and Sefer Shiur Komah.

His solution was simple. He included those written works

within the corpus of the oral mystical tradition. But in order to qualify as an

oral tradition, the three written works must be chanted “in a tune” and

memorized.

This apparently transformed the written word into an oral tradition.

He had another dilemma: Even some of the mystical ideas of

Nachmanides had been written down and some appear in Nachmanides’ various own

commentaries.

Shem Tov Ibn Gaon explained that Nachmanides’ mystical writings were generally

written in a hinted manner and were not explicit:

“[I]n each and every place

[he] hinted at hidden things...based on what he had received. Nevertheless, he

made his words very enigmatic...”

Thus even the mystical writings of Nachmanides were

to be considered essentially as part of an oral and not a written corpus.

PART 3:

THE INTENTIONAL DISORDER OF THE MYSTICAL ORAL TRADITION:

Halbertal explains that indeed Nachmanides and others did

write very sparsely in a hinted and enigmatic style. It seems that they did not do this just to

qualify their writings as technically within the oral tradition but for another

reason as well. That reason was to maintain control over the ideas.

Halbertal writes:

“[The] oral transmission is

not the organized, systematic transmission of Torah secrets... it was also done

through hints, and a little at a time. The student received the chapter

headings and his masters examined how he developed and understood them on his

own; only when he was found worthy did they expand the range of hints and

transmit additional chapter headings, and so on. This method of transmission

provides the masters with long-term control over the learning process, and

enables the process to be halted at various points.”

MYSTICAL ELITISM:

Halbertal elaborates on the difficult conditions imposed on

one who wanted to become a part of the oral mystical transmission:

“The transmission through

hinting, which is gradually amplified in accordance with the student's own

progress, reflects the circular nature of the condition...

The circular conditions of

entry are the profoundest expression of the elitism of the esoteric. One may

not join the esoteric circle, as it is based on a tautology—whoever knows the

secret is worthy of receiving it. Esotericism thus entails a strong sense of

privacy: 'only those who already understand me can understand me'.”

THE ABILITY TO KEEP SECRETS:

The would-be initiate into the world of the oral tradition

of mysticism had to agree to keep his knowledge secret. Shem Tov Ibn Gaon

describes this commitment as follows:

"When they transmitted

(this knowledge) to me, they did so on condition that I would not transmit it

to others except under three conditions, to any one who comes to receive the

matters of the initiates: the first is that he be a Talmudic scholar, the

second that he be forty years old or more, and the third that he be pious and

humble in spirit."

THE POLITICS AND POWER-STRUGGLES OF THE ORAL MYSTICAL

TRADITION:

Halbertal is quick to point out the human reality that is

always present and the tendency for a power-struggle even (or particularly)

within the mystical world:

“An additional restriction

mentioned by Shem Tov — ‘that he be a Talmudic scholar’— was designed to create

a situation in which the realm of closed knowledge would remain the sole

property of the Torah scholars.

This restriction had

institutional and social significance that far surpassed the question of the

student's aptitude for receiving Torah secrets. Esoteric teachings might pose a

threat to authority structures and halakhic frameworks, because they present

themselves as the inner meaning of religion.

The attempt to restrict the

Kabbalah to traditions transmitted amongst Torah scholars is a means of

preventing its becoming a body of knowledge and authority that could compete

with the halakhic world...

The rabbinical elite attempts

to keep the esoteric tradition within its own domain, so that it will not

become a competing institution of authority and inspiration.”

This may be another reason why the mystics of the oral

tradition were not happy with the emergence of the new literary body of written

Kabbalistic literature.

CONCLUSION:

History has shown that the future dominant school of Kabbalah

was to emerge not from the mystics of the oral tradition but from the mystics

of the new written school which included the Zohar.

In this sense, Halbertal concludes:

“Shem Τον Ibn Gaon presents us

with a polemical picture, full and rare, of an esoteric tradition that has lost

its power.”

Back to our original question: who owned the early Kabbalah

- those who wrote it or those who orally taught it?

It seems that initially, it was the elitist mystics of the

school of oral mystical tradition who owned the Kabbalah. But after the

Zohar was published in 1280, the mystical tradition was democratized and opened

up for anyone who knew how to read it.

The new mystical writers now owned Kabbalah

and the older oral school might have felt that the chain they believed went

back to Sinai had been broken. They may also have lamented their loss of control over the mystical literature which now could easily fall into the hands of Kabbalists who could create an opposing stream to the Halachists.

ADDITIONAL READING:

APPENDIX:

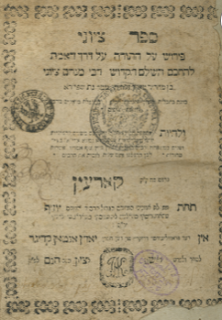

Notes on the picture.

Translation of the title page of Likutim by Rav Hai Gaon (Warsaw 1798 – First Edition Printed by the Magid of Koznitz) which included other works:

[Interesting and relevant names and ideas have been highlighted for further consideration:]

Likutim by Rabbi Hai Gaon, Kabbalistic matters and prayers, "Explanations on the 42 Letter Name, deep secrets, new and very wonderful things", with additional Kabbalistic compilations: Sha'ar HaShamayim by Rabbi Yosef Giktilia, Likutei Shem Tov, Ma'amar Ploni Almoni, on the 10 Sefirot and Names. Tefillat R' Ya'akov Yasgova [of Strzegowo], Sefer Ha'Iyun L'Rav Chamai Gaon, "Secrets by the Kabbalist Chacham Yosef Giktilia" on the mitzvoth, and "Booklet by Rabbi S.T. from the Rashba" explanations of Torah secrets by the Ramban. [Warsaw, 1798]. First edition.

Printed by the Magid Rabbi Yisrael of Koznitz(1737–1814), from manuscripts hidden in his possession, edited by his disciple and personal scribe Rabbi Gavriel of Warsaw. With the approbation of the Magid of Koznitz printed on the verso of the title page. He writes that the manuscript and its printing were performed by his instructions and that Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdychiv also agreed to print the book, "And with the permission of… Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Av Beit Din of Berdychiv".

Perush Haramban, I, pp . 7-8; Chavel, I, pp . 15-16.