|

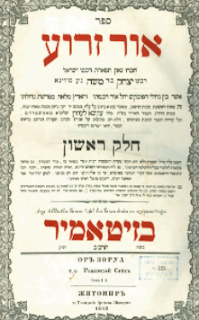

| Depiction of rows of students in the Academy at Sura. |

INTRODUCTION:

Rabbi Professor Yaakov Elman (1943-2018) of Yeshiva

University was one of the pioneer researchers on Babylonian

influences on the Babylonian Talmud. He showed that many concepts such as

astrology, angelology and demonology found in the Babylonian Talmud (Talmud

Bavli) - which are often assumed to be uniquely Jewish - are not found in the

parallel Jerusalem Talmud (Talmud Yerushalmi). Based on this and many

other factors, he concluded that there were many concepts which were popular in

Zoroastrian Babylonia which were adapted and adopted by the Bavli - and

this accounts for their absence in the Yerushalmi and other Palestinian

sources.

“[T]he Palestinian authors of the Talmud

[Yerushalmi]excluded,

almost entirely, the popular fancies about angels and demons, while in

Babylonia angelology and demonology, under popular pressure influenced by

Zoroastrianism, gained scholastic recognition.”

In this article, based extensively on the research of

Professor Jeffrey L. Rubenstein,

we will investigate another difference between the Bavli and Yerushalmi

– their descriptions of the Beit Midrash or House of Study as

well as their cultures of learning.

AGGADA AND BABYLONIAN BIAS:

Rubenstein analyses aspects of Aggada (the narrative

sections of the Talmud) which are particularly found in the Bavli and

not in the Yerushalmi or other parallel Palestinian texts, as these differences

would be good indicators of general Babylonian bias. Narratives are always a

window into the ethos of a society.

Rubenstein writes:

“[W]here we have both a

Palestinian and Babylonian version [of a narrative],

we are on relatively firm ground in identifying the motifs and themes that

appear exclusively in the Bavli version as Babylonian.”

Although there were definite cross-cultural exchanges

between the sages of Babylonia and those of the Holy Land, particularly during

the first four Amoraic (Talmudic) generations, nevertheless, each

culture maintained its unique characteristics and worldview.

We are going to explore how the Bavli accentuated

certain concepts and ideas far more than the Yerushalmi, and we will

analyse why these texts are depicted so differently.

THE HOUSE OF STUDY:

The Bavli emphasises the institution of the Academy,

Study-House or Beit Midrash. What follows are some examples of

parallel Babylonian and Palestinian texts in this regard:

1. RABBI TARFON:

Both the Bavli and Yerushalmi describe the

admirable way in which R. Tarfon honoured his mother.

According to the Yerushalmi:

“Once, the sages came to visit him (R. Tarfon, at

his home)...and she (R. Tarfon’s mother) told them of his (exemplary) deed(s).”

However, according to the Bavli:

“He (R. Tarfon) went and

praised himself (for honouring his mother) in the study house.”

In the Bavli version, it is R. Tarfon and not

his mother who describes the honourable behaviour - and the affair takes place

not when the sages come to visit R. Tarfon’s home but, instead, in the Beit

Midrash.

The Bavli chooses to portray the setting for the

event not at R. Tarfon’s home as per the Yerushalmi, but rather in the Study-House.

2. R. CHANINA BEN DOSA AND THE SCORPION:

Both the Bavli and the (Palestinian) Tosefta

describe R. Chanina ben Dosa being bit by a scorpion (or snake) while praying.

According to the Tosefta:

“R. Chanina was standing and

praying [the Shemona Esrei] when an Arod

[scorpion/snake] bit him. He did not stop praying. [Later] his students went

and found [the Arod] dead on top of [the opening to] his hole. They said, ‘Woe to

the man who was bitten by an Arod, woe to an Arod who has bitten Ben Dosa.’”

However, according to the Bavli:

“He placed his heel over the

mouth of the hole and the Arod came out and bit him, and died. Rabbi Chanina

ben Dosa placed the Arod over his shoulder and brought it to the study-house.”

Again, the Bavli version frames the event as being

connected to the Study-House while the Yerushalmi allows it to

have occurred in the open.

3. CHONI HAME’AGEL (THE CIRCLE-DRAWER):

Both the Bavli and Yerushalmi tell the story

of Choni haMe’agel who was walking along the road and saw a man planting a

carob tree. He asked the man why he was planting a tree which could only be benefitted

from after seventy-years. The man responded that he was leaving it for his

descendants.

The story continues with Choni falling asleep for seventy years

and when he awoke he indeed saw the son of the man who had originally planted

the tree, gathering its fruits.

According to the Yerushalmi:

“When he (Choni ha Me’agel) entered the Temple courtyard (Azara)

it would fill with light.”

However, according to the Bavli, Choni then went to

the Study-House

and it shone with light (or was enlightened) although the sages did not believe

it was actually him after all these years. He died soon thereafter.

Once more, the Bavli introduces the notion of the Study-House

into the narrative while the Yerushalmi allows the events to unfold wherever

they occurred.

PROJECTION AND REFRAMING:

These sources portray a Babylonian predilection towards the Study-House

which is depicted as an organised and large Academy. According to the research

of Jeffrey Rubenstein, David Weiss Halivni, Shamma Friedman and many other

scholars, the post-Talmudic editors of the Babylonian Talmud, known as Savoraim

(or Stammaim) may have reframed and projected their larger and more

public Academies with which they were familiar with, onto the previous Amoraic

(Talmudic) era - where (according to the research) the Amoraim

generally taught in closed scholarly circles; and they taught in Hebrew (not

Aramaic); and their literature and records (as collated by Rav Ashi and Ravina,

the first redactors of the Babylonian Talmud) were in a terse style without

dialectical analysis (shakla vetarya) and similar to the terse style of

the earlier Mishna, Beraita and Tosefta. (See previous

post.)

On this view, it was essentially around the period of the

later Stammaim that the larger Academies and Study-Houses were

put in place. And these Stammaim - while editing the Talmud - projected

the primary role of the Beit Midrash with which they were accustomed,

onto the previous era.

This accounts for why the Bavli, under Stammaic editorship, describes

the Amoraic Beit Midrash or Study-House as a hierarchical

institution with many students, sometimes sitting in rows and rank, with the

more scholarly towards the front.

However, historically we know that this was a

development from the post-Amoraic era of Stammaim (and was even more well-established later by the Gaonim (589-1038).

EXTRA BENCHES IN THE BEIT HAMIDRASH:

The story of the deposition of Rabban Gamliel from his

leadership position of Nasi or Prince, for being disrespectful of

R. Yehoshua, tells of four-hundred (or seven-hundred) extra benches being added

to the Study-House after he had left. They also removed the guard from

the door who had previously kept unworthy students out.

Rubenstein points out that:

“Such descriptions resemble

the rabbinical academy as portrayed in Geonic sources.”

STAMMAIC CULTURAL PROJECTION:

Based on these observations, we have the assertion that the

later editors or Stammaim reframed the smaller more elitist, scholarly and closed

study groups of the Amoraim of the Talmudic period (200-450) to resemble

the larger, more open and public academies with which the Stammaim were familiar.

Such descriptions in the Bavli of huge academies are

predominantly absent from the Yerushalmi.

Rubenstein writes that although there is one(!) source in

the Yerushalmi that describes a large academy (its version of the story

of the deposition of Rabban Gamliel),

besides that source:

“...it is only in the Bavli

where we find descriptions of rabbinic institutions that resemble the highly

developed academies of the Geonic era...

The Stammaim seem to have

functioned in rabbinic academies similar to those described in Geonic sources.”

CHARACTERISTIC DIALECTICAL ARGUMENTAYION OF THE BAVLI:

In many places in the Bavli, we find that its

characteristic style of argumentation and dialectics are lauded as part of good

scholarship. A good sheilah (question) deserves a good teshuva

(answer) and this is officially recognized as a sign of scholastic ability

worthy of a Talmudic sage.

OBJECTIONS AND SOLUTIONS:

When Rav Kahana arrives in Israel from Babylonia, he demonstrates

his academic prowess to the students of Reish Lakish:

“He told them this objection

and that objection, this solution and that solution. They went and told Reish

Lakish. Reish Lakish went and said to R. Yochanan: ‘A lion has come up from

Babylonia. Let the master look deeply into the lesson for tomorrow.”

The Bavli records that Rav Kahana was pushed

backwards in the rows when he fails to object or engage in dialectics, and brought

forward when he does. Dialectics was the very life force of the Babylonian sages.

WITHOUT DIALECTICS THERE IS NOTHING:

In fact, the absence of dialectical argumentation can even

bring death. The Babylonian Talmud records that R. Yochanan died because he did

not have a study partner who could object to and argue with him as Reish Lakish

did.

R. Yochanan bemoans his new study partner, R. Eleazar ben

Pedat, for not engaging sufficiently in dialects:

“Are you (R. Eleazar) like the

Son of Lakish? When I made a statement, the Son of Lakish would object with

twenty-four objections and I would solve them with twenty-four solutions...He

could not be consoled (or: he went out of his mind). The sages prayed for mercy

for him and he died.”

DIALECTICS IN THE YERUSHALMI:

In contrast to the Bavli, Rubenstein writes that:

“ In the Yerushalmi I have

found no comparable stories or traditions that emphasize ‘objections and

solutions’...”

Thus the obsession with study dialectics is a Babylonian anomaly

and not part of the study culture of Eretz Yisrael. It forms the backbone of

the Bavli but is notably absent from the Yerushalmi.

BABYLONIAN ‘STUDY-HOUSES’ AND

PALESTINIAN ‘MEETING HOUSES’:

Although both Bavli and Yerushalmi

do reference the Study-House (Bei Midrasha) and the Meeting-

House (Beit Vaad) - as mentioned, there

certainly was a cultural exchange between Babylonia and Eretz Yisrael - it seems that the Bavli emphasised the Beit

Midrash over the Beit Vaad. The Stammaimic editors of the Bavli

institutionalised the Study-House into a formal Academy, while the Yerushalmi

left it as either Synagogue (Beit Knesset) or general Meeting-House.

AKHNAI’S OVEN:

In the famous story of Akhnai’s

Oven where the river is said to have flowed uphill, the Bavli

records the walls of the Study-House inclined as if to fall – while the Yerushalmi

refers to the columns of the Meeting-House trembling.

BABYLONIAN WIVES ARE MORE OF A

DISTRACTION THAN PALESTINIAN WIVES:

The Bavli often depicts the

wife as a source of distraction from Torah study. There are many cases of

husbands leaving their wives for extended periods of time in order to further

their Torah study.

However, as Rubenstein points out:

“[T]he

tension is less pronounced in the Palestinian parallels...

It appears

that the Bavli stories reflect a more academic and scholastic rabbinic culture

than that reflected in Palestinian sources.

Bavli

stories portray rabbis functioning in a highly structured and competitive

institutional environment.”

MOSHE RABBEINU VISITS THE BEIT HAMIDRASH:

This extremely powerful emphasis on study, besides sometimes

straining the personal relationships within the marital unit, is also reflected

in a narrative concerning Moshe Rabbeinu. Even he is said, as it were, to have battled to

compete within the dialectical Babylonian study culture!

There is a well-known story in the Bavli of Moshe

Rabbeinu journeying forward in time to sit in the academy of Rabbi Akiva (of

the even earlier Mishnaic period). Moshe sat in the eight row together

with the inferior students and he could not understand the discussions taking

place in the rows closer to the front.

ANALYSIS:

Based on the research referenced earlier, the notion of

overflowing academies may have been another projection and reframing of Amoriac

(Talmudic) literature by the post-Talmudic editors or Stammaim (Savoraim).

[See links provided below.]

Not only did the Stammaim reflect the existence of

their larger academies onto the previous Amoraim, but they also introduced

the argumentative style of the sugya which was similarly a projection of

their own style of Babylonian dialectics.

Additionally, the research shows that the Stammaim

introduced Aramaic as the mother tongue of the Talmud, whereas the original

statements as collated by Rav Ashi and Ravina at the close of the Talmudic

period would have been short teachings, in Hebrew, and along the lines of the

earlier Mishna, Beraitot and Tossefta literature.

These post-Talmudic Stammaic innovations largely

distinguish the Bavli from the Yerushalmi which was not subjected

to such editorial activity.

FURTHER READING:

Berachot 33a. Translation: “With regard to the praise for one who prays and

need not fear even a snake, the Sages taught: There was an incident in one

place where an arvad was harming the people. They came and told Rabbi Ḥanina

ben Dosa and asked for his help. He told them: Show me the hole of the arvad.

They showed him its hole. He placed his heel over the mouth of the hole and the

arvad came out and bit him, and died. Rabbi Ḥanina ben Dosa placed the arvad

over his shoulder and brought it to the study hall. He said to those assembled

there: See, my sons, it is not the arvad that kills a person, rather

transgression kills a person. The arvad has no power over one who is free of

transgression.”