|

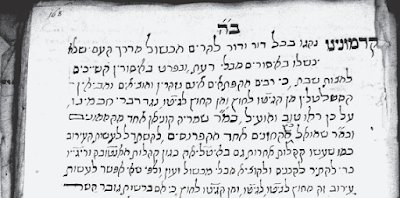

Obadiah the Norman Proselyte who entered the covenant of the God of Israel in the month of Ellul, year 1413 of Documents which is 4862 of Creation

|

Obadiah the Norman Proselyte and Maimonides - a Case of Non-Intersection

Guest Post by Professor Larry Zamick

Introduction

I meet such interesting people through this blog. One such personality is Professor Larry Zamick, a distinguished professor of physics at Rutgers

University in Piscataway, NJ. Born in Winnipeg, Canada in 1935, he attended the

University of Manitoba as an undergraduate and received his PhD in nuclear

physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1962.

In his own words, Professor Zamick describes himself as

“definitely not a Hebrew scholar.” However, his research and findings on the

famous twelfth-century Ovadiah the Ger (Convert) contribute towards, if not

change the way we understand this chapter of Jewish history. It seems that many

confuse two very different Ovadiahs who were both gerim (converts). Some

of the errants are distinguished scholars. The first Ovadiah was a former Christian monk born in Oppido Lucano (Southern Italy) as Johannes, the son of a Norman aristocrat named Dreux. He lived just before the second Ovadiah, a former Muslim, who

is famous for interacting with Maimonides (when he inquired if, in the prayers, he was permitted to refer to Abraham as his 'father').

%20and%2010%20more%20pages%20-%20Personal%20-%20Microsoft%E2%80%8B%20E.png)