|

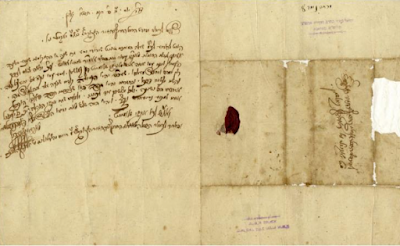

| The Dead Sea Scrolls from around the 3rd century BCE to the 1st century CE |

Introduction

The Hebrew Calendar that we use today has undergone some dramatic transformation over time. What is most interesting is it seems that control over the calendars was often directly related to control over mysticism. In this article, based extensively on the research by Professor Rachel Lior,[1] we examine some of the fascinating developments of the Hebrew Calendar. Much of this information has only come to light in relatively recent times. It must be emphasised that these are Elior's views and not everyone necessarily agrees with the position she takes. Nonetheless, her observations are of great interest.