|

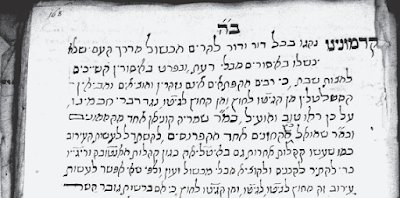

| A section of the Padua eruv document of 1720 discovered by Dr David Sclar. |

Introduction

This article is based extensively on the research by Dr David Sclar[1] who discovered a fascinating document in Padua’s Jewish community archives[2] describing an eruv (a ‘closed off area’ allowing Jews to carry on Shabbat) which R. Isaiah Bassan (a teacher of R. Moshe Chaim Luzzatto) had established in Padua (northern Italy) in 1720.

The Padua Eruv and Rabbi Akiva

R. Bassan established the Padua eruv after being

inspired by his two teachers, 1) R. Binyamin Kohen Vitale (1651-1730) - who

later became his father-in-law - and who had established an eruv in Reggio

Emilia, and 2) Moshe Zacut[3] (1620-1697,

who was the teacher of Vitale) who had made an eruv in Mantua (both were

also in northern Italy).

Ten years later, the Padua eruv somehow signalled

something far more cosmic to R. Luzzatto than a mere closed off area. In a

letter dated 18 Shevat 5490 (1730), R. Luzzatto wrote to his teacher, R.

Bassan, and informed him that he (R. Bassan) was a gilgul

(reincarnation) of the earlier Talmudic sage, Rabbi Akiva (50-135), and

that he had affected a tikkun (mystical rectification) for the soul of

Rabbi Akiva.

Sclar (2017:39) explains that Rabbi Akiva had ruled

unnecessarily strictly on one technical detail of the eruv: He held that

if one threw an object from a private domain, across a public domain, to

another private domain, one would be breaking the laws of Shabbat. The

sages, however, were more lenient and held one to be unaccountable under such

circumstances.[4]

R. Luzzatto claimed that Rabbi Akiva was punished for his

harsh ruling (which needlessly incriminated people who transgressed this law)

by his terrible death at the hands of the Romans.[5] By R.

Bassan establishing his eruv in Padua, according to R. Luzzatto, he was a gilgul

of Rabbi Akiva as he had finally broken his

mystical punishment cycle because it was now easier to observe the Shabbat.

The mystical tikun or ‘rectification’ of the former sage had now been

completed.

The document

The document concerning the Padua eruv which Sclar

discovered in the archives (see Appendix) was not signed. However, it was

written in rabbinic Hebrew which sets it apart from the other documents which

were of a more lay, financial and communal nature. Sclar suggests that either a

scribe or even R. Bassan, the chief rabbi of Padua himself, authored this

document:

“Perhaps Bassan believed that anonymity was better

suited to his motive of ensuring validity” (Sclar 2017:46).

This would have lent the document its required authority to

overcome the inevitable opposition by those who would have objected to the

establishment of the eruv. Although, as Sclar points out, the Padua eruv

required no erection of structures and was essentially ‘invisible’, relying on the

existing architecture for its efficacy.

According to the document:

“The custom to establish an eruv began in my day,

while the leader of our community was Rabbi Moses Zacut (of blessed memory) …”

(cited in Sclar 2017:64).

This is a reference to the earlier eruv that R. Zacut

has established in Mantua, which was one of the precedents for R. Bassan’s eruv

in Padua.

The story behind this document is a fascinating one. Padua

was under Venetian authority and was ruled by a podestà who was in

charge of civilian matters, and a capitano who controlled the military.

Both were appointed by an elected Senate in Venice. This was a democratic

system.

However, the laws of the eruv, technically required

permission from an absolutist (and therefore non-democratic) ruler. Sclar shows

that at least two respona (Sheilot uTeshuvot) from the late seventeenth

century had failed to authorise an eruv granted by a democratically

elected authority. Chacham Tzvi Ashkenazi, for example would not recognise the

Hamburg eruv where permission was only granted by the Burgermeister, who

was appointed by the emperor. Also, Shmuel Aboab of Venice would not recognise

the eruv established in Genoa because permission was only granted by the

protectores.

Jewish law, theoretically, required permission for an eruv

to be granted by every non-Jewish property owner in the vicinity. Because of

the obvious difficulty in achieving such an end, a loophole was found to simply

receive permission for an eruv by the Sar ha-Ir, or ruler of the

city. He was defined as the one authority who could, in a time of war, take

over all the private land including all house properties.

R. Bassan, however, rejected these approaches and maintained

that a republic system of politics was sufficient for establishing an eruv,

and he did so in Padua. The document records:

“Although it may be a common assumption among the

masses that such an eruv would necessitate having the keys of the city handed

over for a short time, this is a total error, as known to erudite individuals.

Therefore, we did not need to do so at all” (cited in Sclar 2017:64).

The Padua eruv document is replete with other interesting

details such as the receiving of permission from the Minister of the Treasury,

who “in his kindness” granted the Jews a fifty-year “lease” of the city. He was

rewarded by being gifted a pair of silk stockings (Jews were involved in the

silk trade), as well as a supply of coffee and chocolate to his officials.

Sabbatian undertones

This document must have had some substantial (rabbinic and

mystical) importance because it was copied,[6]

decades later, by R. Isaiah Romanin, a “messianic colleague of Luzzatto” (Sclar

2017:41), who later became the rabbi of Pesaro.

Sclar writes in a footnote that:

“Romanin copied the text, along with numerous

letters, responsa and poems, in a manuscript that had once belonged to the

kabbalist Joseph Hamits (d. ca. 1676). On the manuscript, see Isaiah Tishby,

“Document on Nathan of Gaza in the Writings of R. Joseph Hamits” (Hebrew),

Sefunot 1 (1956) 80–117.”

This already sets off alarm bells as, all the names of all

the rabbis mentioned thus far (Bassan, Vitale, Zacut, Hamits and Luzzatto) are

all associated with the secret mystical Sabbatian movement that emerged in the

aftermath of false messiah, Shabatai Tzvi (1626-1676).

Sclar, however, is quite sparing in his words and for some

reason does not dwell much on this Sabbatian association, just asking right at

the conclusion:

“What are we to make of the relationship between

Sabbateanism and Italian Hasidism (or pietism in general), considering that

Zacut, Vitale, Bassan, Luzzatto and others were at various points associated

with the heretical movement or its adherents?” (Sclar 2017:63).

Sclar uses the term “Sabbateanism” only once in his 26-page

article[7] which

deals almost exclusively with rabbis tainted by a ‘brush’ with Sabbatianism. Yet,

if I understand Sclar correctly, he still does allude to the strong Sabbatian

influence that pervaded in Italy at that time by his use, of the terms “Italian

Hassidism” and “multi-generational pietists” who were all connected in some way

to R. Zacut a known Sabbatian:

“Luzzatto’s yeshiva…developed within a cultural

environment of Italian Hasidism. In addition to Zacut, Vitale, Bassan and

Luzzatto and his colleagues, a multi-generational network of pietists spanned

northern Italy between the end of the 17th and the middle of the 18th

centuries. The loose network included Abraham Rovigo, Samuel David Ottolenghi,

Aviad Sar Shalom Basilea, Joseph Ergas, David Finzi, Gur Aryeh Finzi, Judah

Mendola and others… these men lived as kabbalist-rabbis. They regularly

participated in halakhic discussions with their rabbinic colleagues, but

otherwise emphasized pietistic practices and kabbalistic study. All were either

directly or indirectly disciples of Zacut, whose reputation as a kabbalist

flourished especially during his time in Mantua (1673–1697). The publication of

his Sod Ha-shem (Mantua, 1743) illustrates the progression if not the success

of the nascent movement: Zacut authored an original liturgical composition for

the circumcision ceremony, which Vitale later commented upon, which in turn led

to the production of supracommentary by Luzzatto’s student Michael Terni. By

the time Luzzatto came of age, Vitale lay at the core of this geographically

dispersed assembly. Zacut’s favored disciple, Vitale became so respected for

his religious devotion that contemporary heresy-hunters tolerated his latent

belief in the messianic validity of Sabbatai Tsevi. He donned tefilin during

afternoon prayers…and encouraged others to do the same. During his later years,

rabbis in Italy came to refer to him reverentially as the “High Priest,” and

Ashkenazic scholars with whom he had never had contact addressed him in glowing

terms of piety (mushlam ba-hasidut)” (Sclar 2017:56-8).

Just the mention of the name Avraham Rovigo is very

revealing of this underlying secret network of Sabbatian followers that had

completely infiltrated the European and particularly the Italian rabbinic

world. Rovigo had studied under R. Zacut. [See Kotzk

Blog: 304) THE DISCOVERY OF RABBI AVRAHAM ROVIGO’S NOTEBOOK OF ASSOCIATES:].

R. Luzzatto himself was suspected to be a secret follower of

Shabbatai Tzvi. He considered himself to be a reincarnation of the biblical

Moses, and his student, Moshe David Valle, to be Mashiah ben David

while Shabbatai Tzvi was Mashiach ben Yosef.[8] [See

Kotzk

Blog: 090) ANOTHER SIDE TO RABBI MOSHE CHAIM LUZZATTO:].

Somehow, this movement of “a multi-generational trend in

Italian Hasidism” (Sclar 2017:42) became interested in eruvin. It seems that

this renewed interest may have been the result of a mystical desire to protect

the community as a whole, something seized upon by the “Italian Chasidim.”

“At its core, the eruv was meant to “spiritually”

rescue transgressors despite themselves…Bassan’s move to “spiritually” rescue

his transgressing flock emerged from a gap between religious ideals and

communal reality. Contemporary rabbinic voices frequently fell on deaf ears, so

he, like Zacut and Vitale before him, chose to rely on otherworldly power to

affect an intractable earthly problem. While the move conveyed a position of

weakness from a social standpoint, Bassan’s self-reliance reflected powerful

conviction. This discrepancy between religious authority and society pervaded

Padua’s communal life and proved fundamental to the development of Luzzatto’s

yeshiva” (Sclar 2017:47).

In other words, because previous attempts to speak

reasonably to the wayward population to change their ways had been unsuccessful,

these (Sabbatian) “pietists” were going to effect the change supernaturally. Sclar

explains that large swaths of Italian Jewish society were not observant of religious

law and:

“a pietist network attempted to both inspire

practically and protect supernaturally, through an emphasis on the mystical. Rather

than living in seclusion, Luzzatto, Bassan, Vitale and other pietists filled

leadership positions or otherwise concerned themselves with the spiritual

welfare of the general Jewish population…Thus, this case study…explores…the

growth of a pietistic elite in 18th-century northern Italy” (Sclar 2017:42).

Before the Padua eruv, in the mid-1720s, R. Luzzato, R. Valle and R. Romanin, “instead of following in a traditional mold” broke away from the Padua community and secluded themselves in private study in Luzzatto’s father’s house. There claimed to have communicated with heavenly beings and were out of the public eye, but were still mystically working for the public interest.

R. Luzzatto clearly believed he was changing the world from within without having to work as a traditional rabbi. In 1729, R. Luzzatto wrote to R. Vitale about his success in spreading pietism in Padua:

“The young men who previously walked in the ways of

youths vanities now, thank God, have pivoted from the evil way to return to the

Lord” (cited in Sclar 2017:53).

Sclar explains:

“His excitement over a perceived improvement in

society, and his inclination to share it with Vitale, stemmed from his belief

that the redemption was imminent and intimately tied to the kabbalistic way of

life he had inherited from the elder kabbalist, through Bassan” (Sclar

2017:53).

Analysis

Remember though, that R. Vitale was more than just a “kabbalist” and

“pietist” and even a suspected Sabbatian! According to Gershom Scholem, R. Vitale

was brazen enough to hang a portrait of Shabbatai Tzvi in his home! (Scholem

1987:275).[9]

So, whose mystical teachings was his student R. Luzzatto

spreading if he inherited his ideas from both R. Vitale and R. Bassan?

Perhaps in response to this, in 1734, Padua’s Jewish

communal board, known as the “Consiglio” passed a resolution (24 to 1) to

institute adult Torah education. All the Padua rabbis, including R. Luzzatto, his

former student R. Valle and R. Romanin were “compelled” to give weekly half-hour

classes to a group of at least thirty men, who were drawn by lot each week.

These were to be “measured by sand” in a hour glass. Wealthy men could excuse

themselves from the sessions provided they sent a replacement. And gambling as

well as private and independent Torah study was not permitted during the lectures!

(Sclar 2017:48).

“[The Consiglio] expected all members of the

community to uphold traditional roles, ceasing personal activities (regardless

of their moral fiber) in order to assemble for a common good” (Sclar 2017:50).

Was this move by the Consiglio prompted by a need to see

their rabbis in action on the community front and not confined within their

inner mystical chambers, or was it to try thwart what they perhaps feared was spread

of Sabbatianism? Did this ‘outreach program’ have to take place under some form

of mainstream supervision to ensure no one was spreading Sabbatianism?

Either way, what strikes one as astounding is that all this activity

was conducted by so many important rabbis and leading “Italian Hasidim,” “mystics,”

“kabbalists-rabbis” and “multi-generational pietists” who were essentially

linked, often in rather direct ways, to the underground Sabbatian movement. Despite

the fact that the Sabbatian movement was officially supposed to have been outlawed

by the mainstream rabbinate since Shabbatai Tzvi was revealed to be a false

messiah when he converted to Islam way back in 1666.

Appendix

A. C. Pa., no. 13, 168 (cited in Sclar 2017:64).

With God’s Help.

From one generation to the next, our ancestors have removed

obstacles from the path of the people so that they not unwittingly stumble into

sin [Isa 57:14], particularly [with respect to] those prohibitions relating to

the Sabbath. Because many simpletons carelessly remove and bring in possessions

from the ghetto to the outside and from the outside to the ghetto, against the

words of our sages, the honorable Shemariah Conian, one of the memunim, and the

honorable Samuel Katz Cantarini, one of the parnasim, saw it good and

efficacious to establish an eruv as had been done in other communities in

Italy, such as those in Mantua and Reggio, in order to permit [people] to carry

items in and out [of the ghetto] without unintentional iniquity. Because the

eruv cannot be constructed from outside the ghetto to within the ghetto or from

within the ghetto outwards except with permission from the Minister of the

Treasury, as is well-known in our law, they went before the honorable

camerlengo, Signore Giacomo Contarini, and informed him of the content of the

request. He graciously heeded their voice and granted the necessary permission

according to the law. Although it may be a common assumption among the masses

that such an eruv would necessitate having the keys of the city handed over for

a short time, this is a total error, as known to erudite individuals.

Therefore, we did not need to do so at all. So the rabbi Judah Briel of Mantua

wrote to our rabbi [Isaiah Bassan], and these are his words: “people can only

dream about having the keys to the city handed over. The custom to establish an

eruv began in my day, while the leader of our community was Rabbi Moses Zacut

(of blessed memory), and there was no other activity except to give one ducat

to his Excellency the Duke, and also, afterwards, [to provide] officials of his

Honor the Emperor with coffee and chocolate.” These were the words of the

aforementioned rabbi. And so, we also gave the honorable camerlengo mentioned

above a pair of silk stockings, and he gave us consent for a 50-year period to

establish the eruv in the synagogue according to the law. And with this,

[people have] permission to carry out and bring in, from the ghetto to the

outside and therefrom to the ghetto, and to carry things throughout the entire

city – except for the Castello, which we left forbidden according to the law

and the enactment of our sages. And so it was on Friday, the eve of the Fast of

Atonement, 5481 since the creation of the world.

[1]

Sclar, D., 2017, ‘An Exercise in Civic Kabbalah: The Establishment of an Eruv

and Its Socio-religious Context in 18th-Century Padua’, Jewish Studies

Quarterly 24:1, 39–65.

[2]

Archivio della Comunità Ebraica di Padova (A. C. Pa.), no. 13, 168.

[3]

Or Zacuto.

[4]

b. Shabbat 4b, 96a.

[5]

b. Berachot 61b.

[6]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Mich. 439 (Neubauer 2239; IMHM F 20522), fol.

138r.

[7]

Twice, if one counts a Bibliographical reference in a footnote.

[8]

See Isaiah Tishby, Messianic Mysticism: Moshe Chaim Luzzatto and the Padua

School. See also a review on the book by Rabbi Dr. Alan Brill, June 2, 2010.

"Pietists" is a translation for Hasidim, correct?

ReplyDeleteWhere does the identification of this term with Sabbateanism come from?

It is not a specific reference to Sabbatianism, as pietists existed in various other forms such as Chasidei Ashkenaz (German pietists of 12th and 13th centuries), and other groups.

DeleteHowever, the Sabbatians were an extremely mystical movement (some say perhaps the most mystical movement in Jewish history) - and particularly the branch that infiltrated the mainstream religious communities, were very pietist in terms of their hashkafot (worldviews) and practices. So not all pietists were Sabbatian but many Sabbatians were pietists.

On the other hand, other factions of the Sabbatians turned to gross impiety and even promiscuity. Some also converted to Christianity and many to Islam; and some somewhere on the periphery like the Donmeh in Turkey.

Then again some of the Sabbatian 'pietists' were also absorbed into, or played important roles in the founding of the Chassidic movement just decades later (Heshil Tzoref and Yakov Koppel for example).