|

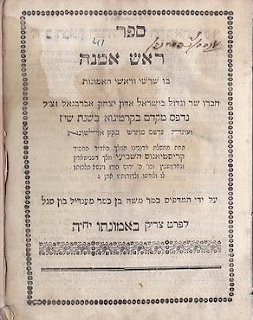

| Ateret Zekeinim (Crown of the Elders): Abravanel's first main work defending the negative image of the biblical elders. |

Part 1

Introduction

There is a

fundamental difference of opinion between Maimonides (Rambam, 1135-1204) and

Abravanel (1437-1508) as to who is entitled to lead the Jewish people.

According to Rambam, it is Moshe (or the relative equivalent in subsequent

generations, which we shall refer to as the “rabbis”); and according to

Abravanel, it is the representatives of the people (which we shall refer to as

the “elders”).

This article is based extensively on the research by Cedric Cohen-Skalli[1] although the adaptation of this debate to modern times is my own.