|

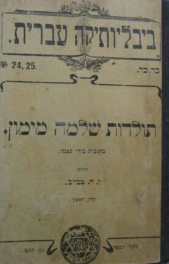

| The Autobiography of Solomon Maimon |

Introduction

This article, based extensively on the research by Professor Immanuel Etkes,[1] looks at the recruiting processes and other activities of the two early Chassidic courts of R. Dov Ber, known as the Magid of Mezrich, and R. Chaim Chaikel of Amdur. Etkes bases himself on two separate texts allegedly presenting an ‘inside view’ and a personal account of the internal world of early Chassidim.

The two texts are:

1) The autobiography of Solomon Maimon which deals

with the court of the Magid of Mezrich).

2) Shever Poshim which deals with the court of R. Chaim Chaikel of Amdur.

Both texts are extremely hostile works. However, Etkes suggests that behind the polemical rhetoric, the intricate details found in the narratives indicate a profound acquaintance of both writers with the personalities, ideologies and practices that they describe. Although the English translations from both texts are a little cumbersome, I intentionally include them for accuracy

1) The account of the court of

the Magid of Mezrich, by Solomon Maimon

The Magid’s court was the first Chassidic court to be established after the passing of the Baal Shem Tov (c.1700-1760). The Magid opened his court in the mid-1760s and it remained in operation until his passing in 1772. The text we consult for the Magid’s court is the autobiography of Solomon Maimon,[2] who spent some time in that court during the 1760s. He wrote his memoirs in the 1790s. Maimon, apparently a young ‘iluy’ (genius), was looking for something deeper than the technical study of the ‘four cubits of the law,’ so he turned to the then-new Chassidic movement. He was, however, disappointed by the Chassidic movement and he started to study Kabbalah but that too held no meaning for him until he found himself in the Haskalah (Enlightenment). Maimon is obviously and blatantly critical of his time in the Chassidic movement but Etkes is convinced that:

“the critical tendency that characterizes his book does not detract from its value as a historical source, for the tendentious slant is transparent and fairly easy to set aside” (Etkes 2005:159).

Maimon describes how he met a young Chassid who was passing through his town. The Chassid told him about the wonders of the new leaders, or rebbes, of the Chassidic movement who:

“could see into the human heart, and discern everything that is concealed in its secret recesses, they could foretell the future, and bring near at hand things that are remote” (Solomon Maimon, Autobiography, 165-67).

His new friend explained to him that the rebbes did not prepare their talks beforehand as the other rabbis did. Instead, they spoke with spontaneity and under inspiration. They did not need to prepare because they felt they were representing the true word of G-d and they were, anyway, united with G-d. They did not give the wisdom but instead simply channelled the teachings. Maimon asked his friend to give him an example of the teachings. The Chassid quoted the well-known verse from Psalms (159:1):

“Sing unto G-d a new song; His praise is in the congregation of saints [Chasidim].”

Then he offered a new Chassidic interpretation: Until the beginning of the Chassidic movement, the praise of G-d consisted of praising His supernatural powers, like His ability to foresee the future and to make manifest that which is hidden. But now, with the advent of Chassidic rebbes, they can do what before only G-d could do, and:

“G-d has no longer pre-eminence over them” (Solomon Maimon, Autobiography, 165-67).

This is why it is now necessary to find a new praise for G-d that supersedes the previous praise of prior generations.

Another interpretation the Chassid shared with the young Maimon was that as long as humans are proactive, they cannot approach G-d. The only way to connect to G-d is to remain absolutely passive, like a musical instrument that only moves when the air or ‘spirit’ passes through it. This is known as bitul hayesh, or self-nullification. Maimon writes:

“I could not help being astonished at the exquisite refinement of these thoughts, and charmed with the ingenious exegesis, by which they were supported” (Solomon Maimon, Autobiography, 167).

This way, Maimon was drawn to a fascinating new type of rabbinic leadership “that deviated from everything previously known in Judaism” (Etkes 2005:162). It is interesting to note that, as Etkes explains, one of the ways of authenticating these narratives is that they correspond to actual Chassidic texts that discuss the same concepts and adopt the same interpretations.

The previous models of rabbinic leadership often comprised Magidim (preachers) and Mochichim (rebukers) who would give talks and lectures as they travelled to the various communities. This changed now, because, with the new model, people travelled to the rebbe, not so much for education but for personal guidance and “holy inspiration.”

Etkes also suggests that it is unlikely that this young Chassid just happened to be passing through Maimon’s town, because it is known that there was an active program of “propagandists” sent as emissaries of the Magid, to recruit particularly young people to the new movement.

Maimon was intrigued by this new approach and fascinated by its daringness and he journeyed to the Magid of Mezrich. He desperately wanted to join the ranks of the new Chassidic movement. He was aware of other Chevrot (societies), like artesian guilds and burial societies which were common at that time and each had some form of official protocol that needed to be observed before membership was conferred. He loved the idea that the Chassidic movement had none of that. Ostensibly, anyone who merely “felt a desire of perfection” could join. But when he arrived at the court, he discovered there was a well-designed protocol:

“At last I arrived…I went to the house of the superior under the idea that I could be introduced to him at once. I was told, however, that he could not speak to me at the time, but that I was invited to his table on Sabbath along with the other strangers who had come to visit him; [I was told] that I should then have the happiness of seeing the saintly man face to face, and of hearing the sublimest teachings out of his own mouth; [I was told][3] that although this was a public audience, yet, on account of the individual references which I should find made to myself, I might regard it as a special interview” (Solomon Maimon, Autobiography, 164).

He followed the instructions and describes a large gathering of people who had come from different places. They all sat waiting for the arrival of the Magid:

“At length the great man appeared in his awe-inspiring form, clothed in white satin. Even his shoes and snuffbox were white” (Solomon Maimon, Autobiography, 164).

They ate the meal in silence and afterwards, the rebbe led them in a “solemn inspiring melody”:

“[E]very newcomer was…called by his own name and the name of his residence, which excited no little astonishment. Each recited, as he was called, some verse of the Holy Scriptures. Thereupon the superior began to deliver a sermon for which the verses recited served as a text, so that although they were disconnected verses taken from different parts of the Holy Scriptures they were combined with as much skill as if they had formed a single whole. What was still more extraordinary, every one of the newcomers believe that he discovered, in that part of the sermon which was founded on his verse, something that had special reference to the facts of his own spiritual life. At this we were of course greatly astonished” (Solomon Maimon, Autobiography, 164).

Etkes analyses some of the social and psychological dynamics at play in this description. The social rituals regulated the time and contact of interactions with the rebbe. No one just walked in and approached the rebbe, as Maimon had expected. Two opposing elements operated almost simultaneously – distance, aloofness and then intense personal contact − and this was experienced by each and every one of the visitors. The late entry does not seem to have been accidental or incidental but rather intentional. It would have created a sense of mystery and drama in which the strangers might have speculated as to what was to happen next, and they would have told each other stories they had heard that drew them to this court. One also notices that special attention was given particularly to the “newcomers,” suggesting that the aim of the gathering was recruitment. But, interestingly, at this stage of the narrative, it seems that Maimon was infatuated and all his expectations of the wonderous rebbe had been met, if not exceeded.

Maimon notes that there was a dramatic show of, and emphasis on, the spontaneity of the rebbe who did not prepare talks like traditional rabbis. Yet every new visitor found some personal resonance with the words of the rebbe and it was not just by listening passively but by an well-structured and individualised two-way correspondence.

As the narrative progresses Maimon begins to question what he had experienced and he becomes rather cynical as he analyses the events that unfolded:

“It was not long, however, before I began to qualify the high opinion I had formed of this superior and the whole society. I observed that their ingenious exegesis was at bottom false, and, in addition to that, was limited strictly to their own extravagant principles, such as the doctrine of self-annihilation. When a man had once learned these, there was nothing new for him to hear. The so-called miracles could be very naturally explained. By means of correspondence and spies and a certain knowledge of men, by physiognomy [the study of facial features][4] and skillful questions, the superiors were able to elicit indirectly the secrets of the heart, so that they succeeded with these simple men in obtaining the reputation of being inspired prophets” (Solomon Maimon, Autobiography, 169).

The “doctrine of self-denial or annihilation,” bitul hayesh, that Maimon references as the cornerstone of the group and around which all else seemed to revolve, was essentially the downgrading of the physical body. To compensate for this, a program was designed to emphasise intense joy and happiness so that one did not feel at all deprived. On the contrary, one felt as if something lofty had been gained.

It was very difficult to maintain this state of ecstasy and the followers lapsed from time to time. To counter these periodic lapses, especially during prayer, Maimon notes that a series of:

“mechanical operations, such as movements and cries, to bring themselves back into the state once more, and to keep themselves in it without interruption during the whole time of worship. It was amusing to observe how they often interrupted their prayers by all sorts of extraordinary tones and comical gestures, which were meant as threats and reproaches against their adversary, the Evil Spirit, who tried to disturb their devotions; and how by this means they wore themselves out to such an extent, that, on finishing their prayers, they commonly fell down in complete exhaustion” (Solomon Maimon, Autobiography, 16-62).

This description portrays a very tangible charm exhibited by the early Chassidic movement which was soon dissipated in the case of Solomon Maimon and he left the group − but for many others, that charm grew and was enhanced as they stayed on and became adherents of the new movement.

2) The account of the court of R. Chaim Chaikel of Amdur,

in Shever Poshim

R. Chaim Chaikel was a student of the Magid and he opened his court just after his teacher’s passing and it remained open until his own demise in 1787. The text we consult for R. Chaim Chaikel’s court is a short pamphlet known as Shever Poshim (smashing of criminals). Shever Poshim is an intense polemic against Chassidism and is attributed to R. David of Makov (although probably not written by him). This writing was produced around 1787 and represents the 1770s and 1780s. Once again, although clearly another hostile work, it matches the patterns of the previous writing of Maimon and the recorded teachings and practices are similarly reflected in parts of Chassidic literature itself.

The writer begins with a quote from the first Chassidic book to be published, Toldot Yakov Yosef.[5] It claims that since a person represents and parallels all the stories in the Torah, they can observe all the 613 mitzvot even though the Temple is not standing:

“In the Torah portion Veatah tetzaveh[6] [and you shall command] we find the following verse: “They shall bring thee pure olive oil” [Ex. 27:20]…And this is a problem: how could this commandment be void in the present, for is not the Torah eternal? And he said that tzav [commandment] comes from the term Tzavta [together, in Aramaic] and [Chibura][7] companionship, and this is how “and you shall command” should be understood: You shall share togetherness with people and bring them to repentance, and then, “ they shall bring thee pure olive oil,” that is to say, they will bring down great abundance for you and public merit, which are the lamps” (Shever Poshim in Wilensky, Chassidim and Mitnagdim, 2:160).

In other words, by showing friendship to Jews removed from Torah practice, you will draw them back to Judaism – and in turn, they will repay you with blessing and light. Thus, the recruitment (kiruv) procedure is a twofold and reciprocal process. Shever Poshim continues to say that while spreading the message of Torah is certainly a worthy practice, the means whereby this is attained in Chassidic courts belies a hidden danger because, in his view, it contains what we today might call a cult-like methodology in that:

“they seek to capture souls among the lesser sons of Israel, with emissaries that they send to all the Jewish cities to incite and to seduce as is their custom, saying to them: Look, we have a new way, which the ancients did not imagine. And moreover, you can cleave to your Maker by means of all the 613 commandments, of which until now you and your fathers only kept a portion. Furthermore, when you go with me to the rabbi in the community of Amdur and the like you will hear from his mouth such and more in this [spirit]” (Shever Poshim in Wilensky, Chassidim and Mitnagdim, 2:160).

This notion of messengers or missionaries believed to “incite and seduce” is corroborated by the written bans against the Chassidim that emerged from Vilna in 1772 and onwards. This was obviously of some, real or perceived, concern at that time. Etkes (2005:173) explains that this fear would clearly have been felt by the older more conservative members of the community in light of the appearance of the new Chassidic movement, but it would have played into the hands of the younger and restless Jews for whom the revolutionary spirit would have been appealing.

Shever Poshim then makes a claim that the Chassidic leadership engage in a disingenuous practice to recruit new members. The emissaries tell the new recruits that they have to confess all their sins before the Tzadik, R. Chaim Chaikel. By giving “pidyon” (redemption) money to a rabbi, he will fix their souls and provide atonement for their previous sins. They then warn the new recruits not to hide anything because:

“if you do not confess and wish to hide something from him, he will tell you, since he knows thoughts” (Shever Poshim in Wilensky, Chassidim and Mitnagdim, 2:161-62).

Meanwhile, Shever Poshim claims that the only reason the Tzadik appears to know details about the recruits is that he has investigated their origins by questioning people (described as “witnesses”) who are familiar with the new member:

“And the fools who are caught in their evil net believe them, because he appoints two witnesses” (Shever Poshim in Wilensky, Chassidim and Mitnagdim, 2:161-62).

Shever Poshim describes the process of collecting redemption money as follows:

“The assistant, who is the inciter in his city and is called Ra ‘ [i.e., ‘wicked’ rather than the usual honorific “Reb” ] Isaac Manshes, remarks to one or another of the Bnei Heikhcalot [new members, particularly the more affluent ones][8] who are there: is it not true that your soul is ill and you require a pidyon [redemption] of the soul? Therefore give a gold coin or more for pidyon of the soul to our rabbi and your transgression will be removed and your sin will be atoned. And in that way the Rabbi makes a very decent living without working at all” (Shever Poshim in Wilensky, Chassidim and Mitnagdim, 2:171).

Shever Poshim acknowledges that some of the monies collected were indeed put back into sustaining the court and the people who have temporarily moved in to live there for some time. In this manner a type of economy was structured whereby:

“The men of means supported those without means” (Etkes 2005:179).

Etkes suggests that for many who remained in the court, it was quite enticing to live close to the rebbe for relatively long periods without financial worries. These visitors became known prestigiously by the title “yoshvim” (those who stay). It was important though, for those who stayed to remain, as much as possible, in a happy and cheerful state of mind. Shever Poshim testifies that sometimes, during the prayers, a worshiper is beaten! This is because, it claims, he wasn’t praying with sufficient joy. And after the beating, the victim and congregants were joyous because:

“grief and sighing had fled and now there is gladness and rejoicing.”

While one may be tempted to dismiss this ‘testimony’ in Shever Poshim as the disgruntled writing of a Mitnagdic opponent to the Chassidic movement, Solomon Maimon correspondingly described a similar event he claimed to witness. It concerned the beating of a man whose wife had given birth to a girl:

“We met once at the hour of prayer

in the house of the superior. One of the company arrived somewhat late. When

the others asked him the reason, he replied that he had been detained by his

wife having been that evening confined with [giving birth to] a daughter. As

soon as they heard this, they began to congratulate him in a somewhat

uproarious fashion. The superior thereupon came out of his study and asked the

cause of the noise. He was told that we were congratulating our friend, because

his wife had brought a girl into the world. ‘A girl!’ he answered with the

greatest indignation, ‘he ought to be whipped.’ The poor fellow protested. He

could not comprehend why he should be made to suffer for his wife having

brought a girl into the world. But this was of no avail: he was seized, thrown

down on the floor, and whipped unmercifully. All except the victim fell into an

hilarious mood over the affair, upon which the superior called them to prayer

in the following words, “Now, brethren, serve the Lord with gladness” (Shever

Poshim in Wilensky, Chassidim and Mitnagdim, 2:169-70).

Shever Poshim points out that when the wealthy men ran out of money, they were sent home. For the others, though, it was made difficult for them to leave:

“a person comes to mingle with them for a year or half a year or at least a quarter of a year, and the longer one stays, the more praiseworthy that is. Sometimes even if he wants to depart fairly soon, [they prevail] against his will by saying to him: you can’t correct anything if you are a hasty man; and if he does not listen to them in that either and wishes to go home, they resort to threats” (Shever Poshim in Wilensky, Chassidim and Mitnagdim, 2:172-73).

Shever Poshim claims they would tell the person who was thinking of leaving that others who had left had experienced bad things on the way home.

Both Maimon’s account and this depiction in Shever Poshim discuss the role the leader’s alleged or projected clairvoyance plays in enticing particularly young members to the new movement. Shever Poshim shows how recruiters, or in its own words, “inciters” would focus particularly on young men:

“It is known regarding their inciters, who incite and seduce young Jewish men to go away with them, which is truly a matter of stealing souls from the people of Israel, that when the inciter is with him on the road, he seduces him and says to him: in your whole life, you have never enjoyed prayer because you have been praying in a whisper without song and without prolonging it, which is not the case with our rabbi... Some sing melodies, and some sing sweetly, and these and those triumph with their voice and attract a person’s heart, so that even if it is stone, it dissolves... And in truth, that gullible man, who comes there and hears the melodies and their pleasant voices − for most of them have pleasant voices and they know how to sing and with their great sweetness − will adhere to them with great love and follow them like a bull to the slaughter” (Shever Poshim in Wilensky, Chassidim and Mitnagdim, 2:173).

Analysis

Whatever one’s views are of the autobiography of Solomon Maimon and Shever Poshim, they certainly are sharp critiques of early Chassidim and their alleged methodology. Some would say that various ideas touched upon in these writings have resonance, to some degree, even to this day, and even outside of the Chassidic movement. Others would reject these writings out of hand, as simply bitter vitriol with no basis in reality whatsoever.

Unfortunately, there is very little wriggle room here,

because if these writings are rare and accurate depictions by eyewitnesses of

life in an early Chassidic court in the late 1700s, then they are indeed

an indictment of the Chassidim of Mezrich and Amdur. And if the writings

are simply exaggerated lies and venomous expressions of hatred, they are

indictments of both those Maskilim and Mitnagdim who produced

them.

[1]

Etkes, I., 2005. ‘The Early Hasidic Court’, in Eli Lederhendler and Jack

Wertheimer, eds., Text and Context: Essays in Modern Jewish History and

Historiography in Honor of Ismar Schorsch, 157-186.

[2]

Solomon Maimons Lebensgeschichte (Berlin, 1792 - 93). English translation;

Solomon Maimonn: An Autobiography. Translated by J. Clark Murray (Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, 2001).

[3]

Square brackets are mine.

[4]

Square brackets are mine.

[5]

Authored by R. Yakov Yosef of Polonne (1710–1784). The section is from Sefer

Toldot Yakov Yosef fol. 64.

[6]

I have transliterated the Hebrew and Aramaic for easier reading.

[7]

Square brackets are mine.

[8]

Square brackets mine, based on Etkes’ explanation in note 26 of a double

entendre intended by this expression.

No comments:

Post a Comment