Introduction

This article, based extensively on the research by Dr Morris Faierstein examines the various accounts of the last night the Kotzker Rebbe spent with his followers in Kotzk.[1]

The popular version

The popular version of the story goes like this: One Friday night in 1839, R. Menachem Mendel of Kotzk (1789-1859) sat with his followers and in front of them he either smoked a pipe or extinguished the Shabbat candles, proclaiming “Leit din veleit Dayan,” (there is no Law and there is no Judge). Thereafter he excused himself from the gathering and secluded himself (or was forced into seclusion by his family) for the next twenty years until his passing in 1859.

Faierstein, however, presents a series of the written accounts that led to this popular version and deconstructs them in an attempt to better understand the evolutionary process behind this story. We will look at six different written sources to see how they depicted the alleged events of that ‘last night in Kotzk.’

1) Alexander Zederbaum (1866)

In 1866, Alexander Zederbaum wrote about a rumour circulating about the Kotzk incident in his Keter Kehuna:[2]

“In his last years a rumour was spread that Anglican missionaries had talked to him [the Kotzker][3] and led him to heresy. Later it became known that this rumour was groundless. He was mentally ill and suffering from melancholia. This is why people were not allowed to see him.”[4]

2) Frenk (1896)

In 1896, A.N. Frenk wrote a novella (a fictional short story but related to facts) in which the main character claimed he was present in Kotzk at a tish (gathering) on that fateful Shabbat night. He tells how the Kotzker Rebbe was agitated and fidgeted in his seat. Then he got up and said:

“My sons, do what your heart desires, for 'there is no Law and there is no Judge!' The gathering was astounded. Menachem Mendel continued, 'you don't believe me? Here is a sign: it is the Sabbath. See what I do!' With these words he grabbed the lit candle.”[5]

Faierstein explains that although Frenk came from a Chassidic

background, he joined the Enlightenment (Haskala) and therefore had a

negative attitude towards Chassidim. For this reason, Faierstein does

not consider his account to be credible.

3) Conflation with R. Baer of Leovo? (1923)

Although Faierstein is hesitant to rely on Frenk’s story, he

does acknowledge that another source, a work entitled Chassidut veChassidim[6] produced

in 1923, speaks of another Chassidic leader − the son of R. Yisrael of Ruzhin,

R. Baer of Leovo − who was similarly involved with the Enlightenment. He touched

burning candles on Shabbat to show that he had lost his faith. Perhaps, Faierstein

suggests, the stories somehow got conflated.

4) R. Slotnick (1920) and the challenges from R. Graubart

and R. Glicksman

In 1920, Rabbi J.L. Slotnick, the general secretary of the Mizrachi movement in Poland, (writing under a pseudonym) published an article[7] in the Mizrachi journal, describing the Kotzker Rebbe as a man unimpressed by miracles and mysticism, and whose two favourite books were Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed and Ecclesiastes. R. Slotnick claims that a copy of Maimonides' treatise on logic with the commentary of Moses Mendelsohn was found in the Kotzker’s bookcase with an inscription that he had taught the book to his children. R. Slotnick further suggested that the Kotzker himself had moved over to the ideas of the Enlightenment.

R. Slotnick explains that the Maskilm (members of the Enlightenment) were interested in the Kotzker Rebbe, and they sent one of their members, a dentist, to work in Kotzk to try to win him over to their side. One day the Kotzker had a toothache and went to the dentist. The rebbe and the dentist became friends, and the rebbe became fascinated by the dentist’s expansive library. He started borrowing the dentist’s books on secular knowledge. The dentist convinced the Kotzker that he could save an entire generation from the ignorance of religion if he made a public display of the truth of secularism.

The Kotzker became agitated, not knowing what to do. His family noticed his distress and sent his main student, R. Mordechai Yosef of Izbica (Ishbitz) to speak to him. The latter arrived in Kotzk on a Friday morning but the Kotzker wouldn’t see him till later in the afternoon. Both decided to go for a walk and to smoke their pipes. Deep in the forest, the Kotzker said:

“How nice the world is. Let's sit and talk for a while” (Slotnick 1920:9).

But the Ishbitzer didn’t want to talk and said he needed to get back in time for Shabbat. The Kotzker returned home upset and did not emerge from his room for the prayers. Just before midnight, however, he made an appearance, and:

“what happened happened ... the heart cannot reveal it to the mouth” (Slotnick 1920:9).

R. Slotnick doesn’t say what happened but there was chaos. Some Chassidim tried to escape through the windows. The only one who remained calm was the Ishbitzer who proclaimed:

“Gentlemen, indeed both the whole tablets and the broken tablets reside in the ark, but in a place where the name of God has been profaned one does not give honour to the master (rav). He's lost his mind. Bind him” (Slotnick 1920:9).

The Isbitzer went to another room where he sat down and began acting as the new Rebbe. After Shabbat he left Kotzk and set up his new court in Izbica. Meanwhile, the Kotzker remained behind, never to leave his room for the next twenty years. The Maskilim (members of the Enlightenment) and the new Isbitzer Chassidim spread the news (albeit with different intentions and motivations) that the Kotzker had become a heretic. Only R. Yitzchak Meir of Gur and his followers remained behind in Kotzk and continued to be loyal to the Kotzker.

As can be imagined, this publication by R. Slotnick (under the pseudonym Y. Elzet) in the Mizrachi journal, created a huge controversy. Some rabbis wanted to excommunicate him for bringing the Kotzker Rebbe’s name into disrepute. The journal soon published a rejoinder by Rabbi J.R. Graubart who argued that the rabbi of Gur, and others, would never have remained loyal to the Kotzker if R. Slotnick’s story was true, and anyway, he argued, it was only the Ishbitzer and R. Tzadok haCohen (both of Lublin) who left Kotzk. The majority of the Kotzker’s main students remained with him.

Twenty years later, Rabbi P. Z. Glicksman wrote Der Kotzker Rebbe[8] to debunk the false story that was gaining traction. It was 1938 and he specifically wrote in Yiddish to reach the widest audience. Glicksman adopted the official Chassidic stance that the alleged Friday night incident never occurred and that R. Slotnick was being disingenuous.

R. Glickman finds some holes in R. Slotnick’s story, including the suggestion that the Ishbitzer was brought in by the family to talk to the Kotzker. Glickman suggests that if anyone could have spoken to the Kotzker it would have been R. Hirsch of Tomoshov who was his gabbai (personal assistant) instead. R. Glicksman also points out that according to both Kotzker and Ishbitzer sources, the Ishbitzer left Kotzk after Simchat Torah in 5600 (not 5599 - 1839) when the incident was to have occurred.

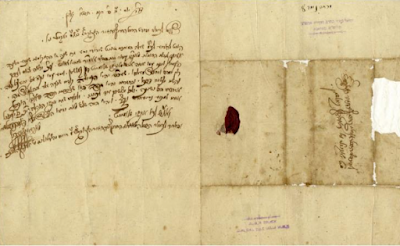

But still, based on available evidence it does seem that something unusual was going on in Kotzk. R. Glicksman himself brings a letter written by R. Yitzchak Meir of Gur (who remained behind in Kotzk) as support for his refutation of the Kotzk incident. The Rebbe of Gur wrote this letter in 1841 to his colleague, R. Eleazar haCohen of Poltuska, who had inquired whether things had quietened down in Kotzk. R. Yitzchak Meir of Gur replied:

“I have just received your letter. This past Sabbath I was in Kotsk and thank God all is well. Three Sabbaths he [the Kotzker] sat with the gathering. The rumours no doubt emanated from accursed evil-doers. In the city of Barzin, one rich man spoke ill [of the Kotzker][9] and the hasidim acted appropriately. They made him pay a fine of 1,000 rubles. Thank God, nothing further was heard of the matter.”[10]

This letter can be used to swing the argument both ways. Sure, things were fine now − in 1841, two years after the alleged incident of 1839 − but two years later there were still “rumours” floating around.

Furthermore, Glicksman claims that the stories of the Kotzker

Rebbe’s isolation for twenty years were grossly exaggerated. He maintains

that during that period, although the large gatherings had stopped, the Kotzker

continued to meet with his close students and, on Shabbat, he regularly

tested his grandsons on their studies. −Again, this evidence is ambiguous. In

fact, it seems to corroborate the impression that something was amiss and

things were indeed no longer normal. Granted, the Kotzker saw a few

people so he wasn’t totally isolated, but why did the large gatherings suddenly

cease?

5) Joseph Opatoshu’s novel (1915-1919)

Around 1919, Joseph Opatoshu published his novel, In Poilisher Velder (In Polish Woods).[11] This story was published before Slotnick’s article in the Mizrachi journal, so it must be seen as standing independently from it. Faierstein informs us that this book was one of the most popular Jewish novels of the interwar period. In this widely read piece of literature, no mention is made of the Kotzk incident, but there is a reference to a forced solitude imposed upon the Kotzker by his family members:

“His intimates feared lest, with his interpretations of the Torah, the Rabbi (Menachem Mendel) might alienate the few remaining adherents. So they watched over him, and kept all strangers at a distance.”[12]

Although the following words are put into the mouth of a fictional character, the insinuations (either made up or based on some form of oral tradition) are palpably disturbing:

“Now is the time, Rabbi of Kotsk, for you to do penance! Your intellectual followers are selling their phylacteries. They say that this year leather has been very cheap in Kotsk. Such upstanding Jews as Hirsh Partzever and Hayyim Beer Grapitzer have taken an example from you, Rabbi, and agreed among themselves not to put on their phylacteries for three days. They wanted to see what effect this would have upon the order of the universe.”[13]

The book continues to paint a picture of Kotzk being influenced by another fictional character, Daniel Eibeschuetz (a hint at R. Yehonatan Eibeschuets who was accused by R. Yakov Emden of being a secret follower of Shabbatai Tzvi). The implication is that some form, not just of Enlightenment, but of antinomian Sabbatianism or Frankism, was at play in Kotzk.

In Poilisher Velder was so popular that in the first ten years, it was translated into six languages and went through ten editions. Most of the reviews praised the book, although clearly a novel, for its general historical accuracy. Even “so eminent a historian as Meir Balaban devoted an article to the novel's historicity” (Faierstein 1983:185). The Chassidim of Poland, however, ex-communicated the author and banned his book. When the book was made into a movie in 1928, its premier in Warsaw was greeted with a riot by Chassidim.

In a communication between the author, Joseph Opatoshu and

R. Glicksman (who, as we saw, had also challenged R. Slotnick), Opatoshu did

admit that he used poetic licence while writing his book and that it was not strictly

intended to be a historical work.

6) Martin Buber (1922)

In 1922, Martin Buber wrote a book[14] where he depicts the Kotzk incident as taking place, not on Friday night, but rather on Shabbat afternoon, during the Third Meal (Seuda Shlishit):

“Buber relates that Menachem Mendel rose and began to say that man is a part of God. Man has desires and lusts and these too are a part of God” (Faierstein 1983:186).

Buber then says that the Kotzker declared that there is no Law and no Judge, and then remained in seclusion for thirteen years. Faierstein suggests that Buber got confused between the thirteen years the Kotzker served as a Rebbe, and the twenty years of his seclusion. Buber, on the other hand, claimed he took his version from an oral tradition he had received.

Faierstein, however, points out that in Buber’s revised edition of his work, The Tales of the Hasidism,[15] he gives an entirely different version of the Kotzk incident, based on Slotnick’s version, and:

“The debt to Slotnick is not acknowledged, nor is the radical disparity between the two versions accounted for” (Faierstein 1983:186).

This, according to Faierstein, would rule out Buber as a reliable historic account.

Conclusion

Faierstein does mention that politics may have played some role in the spread of the different versions of essentially the same story. Frenk was no friend of the Chassidim. Slotnick was the general secretary of Mizrachi at a time when Mizrachi was engaged in a conflict with Agudat Yisrael, which was headed by the Rebbe of Gur (the spiritual ‘heirs’ of Kotzk). Thus R. Slotnick may have had an axe to grind.

Faierstein concludes that the Kotzk incident has:

“no real factual basis. How it came into existence and gained popularity remains a subject of speculation” (1983:189).

Analysis

The great irony is that of all the Rebbes, the Kotzker stood for uncompromising truth. Truth was to be truth and one would imagine that facts were to be facts. Yet it is so difficult to ascertain the truth and the facts about the last twenty year period of his life.

Of course, an alleged event of some sort − taking place in Kotzk in 1839; at midnight on Shabbat; in the presence only of Chassidic followers; involving perhaps some form of a political breakaway; and resulting in a twenty-year seclusion period for their Rebbe – would be very difficult to document for its historical accuracy even one week later.

Regarding the problem that all we really have are 'outside' (secular) sources, as we have seen - one wonders whether 'internal' (Chassidic) sources would be any more beneficial to establishing the facts.

For example, the printed version of Shivchei haBesht which is the Chassidic biography of the Baal Shem Tov, records that the Baal Shem Tov once said that Shabbatai Tzvi had a ניצוץ קדוש (spark of holiness) in him. However, according to the original hand-written manuscript, the claim was far more dramatic: Shabbatai Tzvi had a ניצוץ משיח (spark of the Messiah)! The printed version, in its attempt at toning down this overt messianic reference, provides no editorial notification of this fundamental discrepancy. The editors and printers were obviously very aware of the original manuscript version but they did not indicate that they had changed the text. We would never have known of this very controversial messianic reference to Shabbatai Tzvi, in the name of the founder of the Chassidic movement, were we not able to compare it to the original version in the manuscript.[16]

Chassidic sources are generally good at establishing dates of the reigns of the dynasties, lineages, places, and teachings, but are highly censored when it comes to fundamental principles that sometimes collide with their Hashkafa (worldview).

So, unfortunately, instead of facts, all we are left with regarding the alleged incident of the 'last Friday night in Kotzk' are kernels of a strange story. And kernels can easily be spun in any direction.

Further Reading

Kotzk

Blog: 147) THE (UNCUT) STORY OF KOTZK - A REVOLUTION WITHIN THE CHASSIDIC

MOVEMENT:

[1]

Faierstein, M.M., 1983, ‘The Friday Night Incident in Kotsk: History of a

Legend’, Journal of Jewish Studies, 34, 179-189.

[2]

Odesa, 1866.

[3]

Parenthesis is mine.

[4]

Keter Kehuna, 132.

[5]

Frenk, A.N., 1896, ‘miChayei haChassidim bePolin’, in Sifrei Agurah, vol.

III, Edited by Ben Avigdor, Warsaw, 82.

[6]

Horodetsky, S.A., 1923, Chasidut veChasidim, Dvir, Berlin, III, 125.

[7]

Slotnick, J.L., (Y. Elzet), 1920, ‘Kotzk’, Hamizrachi, vol. 11 no. 14,

Warsaw, 7-10.

[8]

Gliksman, P. Z., 1938, Der Kotsker Rebbe, Piotrikiv, 61.

[9]

Parentheses are mine.

[10]

This leter was first published in Meir Einei haGolah, Piotrikov, 1928,

paragraph 359.

[11]

Originally, it came out in both Hebrew and Yiddish, and was later translated into

English, In Polish Woods (Jewish Publication Society; Philadelphia, 1939).

[12]

In Polish Woods, 190.

[13]

In Polish Woods, 202.

[14]

Buber, M., 1922, Der Grosse Maggid und Seine Nachfolger, Frankfurt.

[15]

New York, 1948.

[16] Liebes, Y., 2007, ‘The Sabbatian Prophecy of R. Heshil Tzoref of Vilna in the writings of R. Menachem Mendel of Shklov, the student of the Gaon of Vilna and the founder of the Ashkenazi settlement in Jerusalem’ (Hebrew), Kabbalah 17, Idra Press, Tel Aviv, 107-168 (1-91), 14 footnote 79.

In Martin Buber's work "Schriften zum Chassidismus" (1963) we find an interesting story: The Chozeh & the Magid of Kozenitz are debating the coming of Moshiach, when a young Menachem Mendel (the future Rebbe of Kotzk) interferes with an objection. He gets reprimanded by the Chozeh for interrupting a discussion by the two older Rebbes. Throughout the book, the discussions about the Napoleonic war and the resulting impending coming of Moshiach takes an inordinate importance in the then leaders' minds. I always wondered if the frustration about the "tarrying" of Moshiach's coming did not impact the emotional wellbeing of the Kotzker.

ReplyDeleteDo you remember what his "objection" was said to have been?

DeleteDear Rabbi Michal, In response to your request, I made a picture of the pertaining page in Buber's book. Please email me your contact & I am happy to send it to you yehuda@menchens.ca

ReplyDelete