|

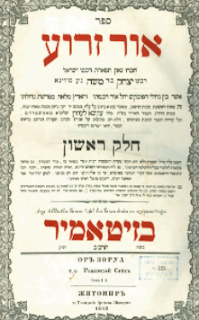

| The first mention of mourners reciting Kaddish is found in the 13th century Or Zarua |

Introduction

Most discussions on the origins of the Mourner’s Kaddish

as we know it today, only begin from around the twelfth century in Germany. It

was there that the Kaddish - which had existed from much earlier times

although not necessarily relating to mourning - was finally institutionalised

as mourning ritual.

This article, based on the research by Professor David Brodsky[1], traces the development of the now widespread custom of reciting Kaddish for beloved ones who have passed away, and explores where the idea originates that a child can ‘redeem’ a deceased parent.

The origins of the custom of reciting Kaddish

Around the twelfth century, the custom began to ‘recite Kaddish.’

This custom originated in Germany and the Kaddish was only recited once

a week, after Shabbat, on Saturday night.[2]

According to Machzor Vitry (114):

ועל כן

נהגו לעבור לפני התיבה במוצאי שבת אדם שאין לו אב או אם לומר ברכו או קדיש

Therefore, the custom was for a person who did not have a

father or mother to go before the ark [i.e., to lead the service][3] on

Saturday night to say the barkhu or Kaddish.

The Machzor Vitry, which was written by a student of

Rashi, R. Simcha ben Shmuel of Vitry (d.1105), mentions this custom after

prefacing it with the story of a rabbi who came across a dead man suffering in

hell. The man asks the rabbi to locate his pregnant wife and to promise to circumcise

his son and teach him Torah. In newer versions, the rabbi is said to get the

son to recite Kaddish (or Barechu). Later when the rabbi again

meets up with this man, he is told that because of these actions, he is no

longer suffering in hell.

Babylonian sources

Besides the Machzor Vitry, there are other sources as well (seventy versions! according to Rella Kushelevsky 2004) and they all refer to an earlier event usually identifying the rabbi as R. Akiva. What is interesting and important to note, though, is that the earlier sources are exclusively of Babylonian origin and hail from the Amoraic or Gemara period (220-500 CE). In these earlier sources, though, there is no mention of Kaddish or for that matter any other particular prayers that needed to be recited.

However, as a general rule, the sources from Palestine

do not concur with the belief that others can intercede on behalf of someone

who has passed away:

Palestinian rabbinic Judaism tended toward the belief that,

while people may repent up until the very last moment of life, once dead,

nothing further can be done (Brodsky 2018:337).

This distinction between Babylonian and Palestinian sources

is most significant because they may indicate some Persian, Sassanian and

Zoroastrian cultural influence on the origins of this custom, something that

did not exist in Palestine.

Brodsky (2018:337) explains:

Rather, that story is consistent with its larger Sassanian

(Zoroastrian) cultural context in considering the son to act as an extension of

his father (while the son is still a minor), and therefore his good and bad

deeds still do contribute to his father’s ledger even though his father has

already passed away…

Babylonian rabbinic texts…reflected a belief that the son is

both able and obligated to help his father’s case in heaven through the

former’s deeds.

In Sassanian and Zoroastrian culture the child graduates from

the minor status at the age of fifteen, when he becomes an adult. Until then, his

actions are under the jurisdiction of the father. This is why his deeds,

particularly as a minor, can ‘redeem’ his deceased father who continues to hold

the ‘rights’ to those deeds.

But this belief was generally not held by Palestinian or Yerushalmi

sources. The question then becomes just when did Judaism accept that someone

else’s repentance, or even someone else saying a prayer could alleviate the

deceased’s condition in the afterlife?

Brodsky (2018:337) answers this question by showing that:

Babylonian rabbinic theology is consistent with its

Zoroastrian Persian cultural context.

Yet, fascinatingly, a pattern begins to emerge whereby the

Babylonian rabbis try to root their adoption of Babylonian cultural concepts,

not in Babylonia but in sources from Eretz Yisrael!

Curiously, though their theology was Babylonian, these

Babylonian rabbinic sources designated their position as of Palestinian origin.

As with most of the cases…in which Babylonian rabbinic Judaism was faithful to

its Babylonian cultural context, it conspicuously attributed its Babylonian

theology to Palestinian sources, though actual Palestinian sources belie this attribution.

The idea that someone else can affect

a change in the status quo of the afterlife of a deceased person is absent from

late Second Temple, Tannaitic, and Amoraic rabbinic Palestine. It is found,

however in Amoriac Babylonia. This means that before around 220 CE (which is

when the Amoraic period begins) there is no real rabbinic concept of vicarious

redemption of a deceased’s soul by some activity on the part of another. And

from 220 CE, this idea is found only in Babylonia.

Palestinian sources

Palestinian rabbinic sources strongly

maintain that a person can atone for their sins up to their last breath. These

sources are scattered in the Tosefta, Yerushalmi, Kohelet

Rabba (known to frequently draw upon the Yerushalmi, and the sources

from the Bavli were added at a later date), Ruth Rabba, and Avot

de Rabbi Nathan.

So, for example, Tosefta on Kiddushin

1:15 reads:

ר׳ שמעון אומ׳ היה אדם צדיק כל ימיו

ובאחרונה מרד איבד את הכל שנ׳ צדקת הצדיק לא תצילנו ביום

רשעו

R. Shimeon says: If a person was righteous all his days, but

in the end he rebelled, he lost it all, as it is said, “The righteousness of

the righteous will not save him on the day of his wickedness” (Ezek 33:12). If

a person was wicked all his days but repented in the end, God receives him, as

it is said, “And the wickedness of the wicked, he will not be weakened by it on

the day that he returns from his wickedness” (ibid.).

According to this Palestinian source,

everything depends solely on the individual him or herself and neither the best

of the best nor the worst of the worst will be able to save or harm them once

they have departed, and there is no option of vicarious assistance or

redemption.

According to Kohelet Rabba

7:15:

כל זמן

שאדם חי הקב״ה מצפה לו לתשובה, מת אבדה תקותו שנאמר (משלי יא:יז) במות אדם רשע

תאבד תקוה

So long as a person is alive, the Holy One Blessed Be He

awaits his repentance, but once he has died, his hope is lost, as it is said,

‘with the death of a wicked person, hope will be lost’ (Prov 11:7).

This Palestinian source also

indicates that once a person passes away “all hope is lost” and it is futile

for someone else to think they can still redeem them.

The Yerushalmi Berachot

9:1,13b similarly states:

.. All one’s life there is surety, for so long as a person is

alive he has hope, but, once he has died, his hope is lost.

Avot de Rabbi Natan (B 27), yet another Palestinian

source, writes:

Just as a person cannot share the reward with his fellow in

this world, so a person cannot share the reward with his fellow in the World to

Come…Just as Abraham could not save Ishmael nor Isaac save Esau, so no one can

repent for and save anyone else.

It must be mentioned that Brodsky

(2018:341-349) does deal, in quite a convincing manner, with some apparent exceptions[4] and

questionable Palestinian sources that seem to negate this notion. It does,

therefore, appear quite clear, from Palestinian sources, that a rule emerges that

there is no vicarious redemption for one who has passed on, even by someone’s

own children.

Babylonian sources

Some Babylonian sources do continue

with this Palestinian notion that no one can save another in the afterlife but,

for the main part:

Babylonian sources consistently adjust this Palestinian

material to fit a Babylonian theodicy that allows the living to help the dead

in certain circumstances, especially for children to give merit to their

parents (Brodsky 2018:349).

So we see, for example, that the

Palestinian source of Avot de Rabbi Natan, quoted above, where Avraham

cannot redeem Yishmael and Yitzchak cannot redeem Eisav – the Babylonian Talmud

(Sanhedrin 104a) uses these same examples to make a very different point:

ברא מזכי אבא, אבא לא מזכי ברא

The son makes the father meritorious; the father does not

make the son meritorious.

Now we begin to see, in Babylonian sources, the idea of a son

being able to make his deceased father meritorious. Brodsky (2008:350-1) points

out:

The parallel is rather striking, and the Bavli would seem to

be reinterpreting this earlier Palestinian tradition… In the hands of the Bavli, these two

examples are taken for what they have in common: fathers cannot save their

sons. By implication, then, sons could perhaps save their fathers!

While Palestinian sources, as we saw

earlier, state explicitly that there is no hope after death, Babylonian sources

generally reject that. The Babylonian Talmud (Kiddushin 31b) speaks about the honour a

child must show to his or her father, and states as one example:

If a person repeats a saying he heard from his [father’s]

mouth, he should not say, “Thus said father,” but rather, “Thus said father, my

lord, may I be an atonement for his rest.” And this applies only within the

twelve months [after his father died], from here on out, [he should say], “May

his memory be for life in the World to Come.”

This Babylonian text espouses the

view that a child can and should try to bring about an atonement for the father

during the first twelve months of his passing. Twelve months is considered to

be the maximum time one can spend in gehinom (hell).

One of the earliest of the seventy versions of this

story of R. Akiva’s encounter with the

tormented soul from hell is recorded in Kallah Rabbati 2:9 in Babylonian

Aramaic, but by having R. Akiva (spelled with an “afef” in the

Babylonian Talmud and a “heh” in the Jerusalem Talmud) as the subject, it

seems:

to be attempting to give an aura of Tannaitic Palestinian

authority to a notion that we find exclusively in Amoraic Babylonian sources (Brodsky

2018:353).

This version describes R. Akiva going

to “that place” - hell - and encountering a tortured man who had committed

every imaginable sin while he was still alive. This story has Babylonian

overtones as the punishments with which the dead man is being subjected to

corresponds to the Zoroastrian context of punishment in the Ardā Wīrāz-nāmag.

The later versions of this story loose some of the overt resemblances to

Babylonian and Zoroastrian culture. This Kallah Rabbati version tries to

set the story in a Palestinian context but it clearly goes against the grain of

Palestinian rabbinic theology. Later versions have the son even reciting the Kaddish.

Since previous scholars had not recognized the primacy of the

version of the story in Kallah Rab. 2:9, they missed that the story was not

originally focused on an expiatory prayer, and that it only later morphed into

the barkhu and then the Kaddish (Brodsky 2018:358).

Zoroastrian

and Babylonian cultural traditions

The prevailing Sassanian Babylonian

culture, unlike the rabbinic theology of Palestine, believed that children

could redeem their dead parents.

Zoroastrianism does allow certain posthumous acts to help the

soul reach a better destination in the afterlife. Indeed, it is incumbent upon

the heirs of the deceased to labor for the soul of the deceased (Brodsky

2018:363).

According to the Babylonian text Dādestān

ī dēnīg:

If he who has passed away did not order that good deed, and

did not also give instructions for it, but it (i.e. the good deed) was (done)

by means of his property and (it was) in conformity with what may have been

done (by him) in his lifetime, (then it) reaches (him) … to improve his

position.

And according to Zoroastrian text Šāyist

nē šāyist (10.22):

“Make a big effort to produce children only in order to

accumulate more good deeds!” For…good deeds performed by a son will become just

as if one had performed them with one’s own hands.

According

to Rivāyat of Ādur Farnbāg 141.2:

And in every chapter which is regarding atoning for one’s

father’s sins and the good deeds also for the father’s soul, when one expiates

for one’s father’s sins, guilt, and debts, it is better to perform services for

the father’s soul…

Thus, we see that Babylonian culture

strongly maintained an ideology of a child - particularly a minor because the

father still has rights of ‘ownership’ of the minors deeds - who is able redeem

his father.

Or Zarua on a minor saying Kaddish

There is a recounting of the ‘R.

Akiva story’ in the Or Zarua[5] (by R. Yitzchak ben Moshe of Vienna, one of Chassidei Ashkenaz) followed by a statement from Tanna de’ve’Eliyahu, that it is

specifically a minor child, under the age of bar mitzva, who while

leading the public prayer service, can atone for his deceased father’s sins.

This has always been a rather perplexing idea because according to Halacha,

a minor cannot lead the prayer services.

This has led Ta-Shma[6], for

example, to suggest that the custom developed, shockingly, in the wake of the

Crusades because so many minors were suddenly orphaned. But Brodsky (2018:366)

suggests that:

The Sassanian context of this story may finally explain how

and why this custom might have developed: because the child is a minor, the

merit goes to the dead father… While the story did not itself originally advocate the practice of the

Mourner’s Kaddish, the later could not have developed without the theological

impetus of this Sassanian context.

And Brodsky (2018:369) sums up the

development of the practice of reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish, as

follows:

In this way, we must see the Mourner’s Kaddish as the product

of several cultures—Jewish and Zoroastrian, Palestinian and Babylonian, late

antique and High Middle Ages—all coming together to produce this unique custom.

Yet it seems that had the Palestinian

sources not given way to the later dominance of the Babylonian sources (as we

see with the Talmud Yerushalmi acceding to the Babylonian Talmud) we may

never have been able to develop arguably the most practiced Jewish custom, where a child 'redeems' a deceased parent's soul by reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish.

Further reading

Kotzk

Blog: 256) WHY DID THE MOURNER’S KADDISH SUDDENLY EMERGE DURING THE 12th

CENTURY?

Kotzk

Blog: 197) BABYLONIAN INFLUENCES ON THE BABYLONIAN TALMUD:

Kotzk

Blog: 149) REVENGE OF THE TALMUD YERUSHALMI:

Kotzk

Blog: 200) “THE TALMUD OF PERSECUTION” vs “THE TALMUD OF EXILE”:

[1]

Brodsky, D., 2018, “Μοurner’s Kaddish, The Prequel: The Sassanian-Period

Backstory Τhat Gave Birth to the Medieval Prayer for the Dead”, in The

Aggada of the Bavli and its Cultural Worlds. Edited by Geoffrey Herman and Jeffrey

L. Rubenstein, Brown Judaic Studies, 335-369.

[2] This

was a ritual for Saturday night after the Sabbath departed because there is a

Jewish tradition that the dead are not punished in hell during the Sabbath.

[3]

Parenthesis is mine.

[4] Two

possible Palestinian source exceptions are Channah for the congregation of Korach

and R. Meir for Elisha b. Abuya. Yet this still underscores the principle that

unless we are Channah or R. Meir, “the rest of us can do little if anything

to change the fate of the dead” (Brodsky 2018:349).

[5]

Or Zarua, chelek bet, hilchot shabbat, siman 50:

[6]

Ta-Shma, “Kezat ‘inyanei kaddish yatom,” 306–7.

Hello, I've juste discovered this wonderful blog and all the highly interesting material you bring up there a few weeks ago and I've been reading all that I could from you

ReplyDeleteIs there an e-mail we can write you on ?

In particular you've said you were working on an article dealing with the documentary hypothesis that really interests me. Could you send it to me ?

Thank you very much

Betsalel

(betsalelbellicha@gmail.com)

Hi Betsalel,

ReplyDeleteMy email is baalshem@global.co.za

Thank you.

Very interesting! Did you see the chapter on this in my book Rationalism vs. Mysticism?

ReplyDeleteHope all is well with you!

Thank you Rabbi Dr. Slifkin. I have always maintained that without your groundbreaking research on Rationalism and Mysticism it is impossible to undertake any serious study of Jewish theology and hashkafa. Before you, not too many people were even aware that such ideological poles even existed. Each pole went on to inform much of future Judaism. Without the clear distinctions you have pointed out, everything merges into just a montage and blur (albeit a comforting one). Serious Jewish scholars will always be indebted to you in this regard, let alone your other contributions.

ReplyDelete