Introduction

The length,

breadth and depth of classical rabbinic thought continues to fascinate and

intrigue me unabatedly. One such rabbinic figure is that of Abravanel (1437-1508),

who, the more one reads about, the more complicated a personality he becomes.

We noted in an earlier article that Abravanel is difficult to define as being either a rationalist or a mystic as he seems to vacillate between the two approaches. This article, based extensively on research by Professor Eric Lawee[1], explores Abravanel’s complexity even further.

Traditionalist

or disrupter?

Besides our

uncertainty as to Abavanel’s relationship with mysticism (he wrote three

messianic works during a short window in his life and he never returned to the

subject) – there is also the uncertainty as to the nature of his relationship

with tradition. At times he appears to be a great defender of tradition but

then he sometimes responds boldly and assumes a more critical role, and other

times he become quite innovative. Lawee (2001:6) describes this latter streak

in Abravanel as follows:

“Abarbanel’s approach to sacrosanct figures and his readings of

classical Jewish texts could be decidedly, and at times quite wittingly—nay,

provocatively—'untraditional.’”

So, for

example, Abravanel rather sarcastically defines the “characteristic

expression of Jewish thinking about truth”[2] as

simply “always referring back to something earlier.”[3]

Abravanel’s

open use of non-Jewish sources

Although

Abravanel did most of his writings while in Italy, most of his life was spent

in Spain and there is a very distinct Iberian influence on his thinking and

methodology. Many Jews who had previously lived in Muslim (southern) Spain,

known as Andalusia, moved further north to Christian Spain and brough some of

their Andalusian influence with them.

The Muslim

south and Christian north divide brought with it some tension because centuries

earlier, some Jews, like the family of Rambam (1135-1205) chose to remain

within the Muslim sphere of influence and they embraced much of that ideology,

especially the Greco-Arabic scientific and philosophic writings.

In time, however,

some of this Andalusian influence, particularly in regard to poetry, scriptural

interpretation and philosophy, was lost within northern Spain. Many

Hispano-Jewish rabbis adopted and encouraged the emulation of some Christian

approaches, including respectful decorum in synagogue and attentiveness during

sermons. This warming to the Christian culture of northern Spain brough with it

an appreciation for:

“for a number of Latin theological, philosophic, exegetical, and

historiographic achievements… Some Hispano-Jewish litterati even sought to make

precious Latin finds, like works of Thomas Aquinas, available in Hebrew

translation. Among Iberian scholars, however, few if any rivalled Abarbanel for

broad immersion in Latin literature” (Lawee:2001:28).

In his

introduction to the Former Prophets, Abravanel points to his familiarity with

Christian biblical interpretation. He says that he will “divide each of the

books into pericopes [sections][4]”

smaller than those devised by Gersonides (R. Levi ben Gershom or Ralbag) but

larger than those sections devised by “the scholar Jerome, translator of

Holy Writ for the Christians” (Lawee 2001:37).[7]

In

Abravanel’s commentary on Samuel (204–205), he shows familiarity with fourteenth

century converso churchman, Paul of Burgos. A few pages later he refers to the

Vulgate (the Latin translation of the Bible, produced by Jerome of Stridon who,

in 382, was commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Vetus Latina Gospels

used by the Roman Church). Elsewhere, Abravanel writes of Augustine as the ”greatest

of the Christian Scholars”. Then he makes use of an interpretation which is

confirmed by “all the gentile scholars and adduced by the scholar Thomas in

his work entitled Secunda secundae.” [Samuel 295–97]

Abravanel

also borrowed extensively from Spanish Franciscan Alfonso de Madrigal, “el

Tostado.” Lawee (2001:39) writes:

“Even if a Hebrew translation of Thomas’ De spiritualibus

creaturis ascribed to Abarbanel never existed, one notes a couple of formally

laudatory references to Thomas (some censored from standard printed editions of

Abarbanel’s Deuteronomy commentary)…”

Surprisingly,

more “faith-based”[8] interpretations from Christian scholars, were sometimes

preferred by Abravanel over some rationalist rabbinical interpretations. Ralbag

interpreted the stoppage of the sun in Joshua 10 as metaphorical. To Ralbag’s

mind, the sun did not actually stop in the sky, but it was rather a poetic

description of the victory that had occurred so swiftly and was as if the sun

had stopped. Lawee (2001:40) explains’

“Advocating a more faith-inspired religious stance than the one

mustered by Gersonides and other late medieval Jewish rationalists, Abarbanel

lauded the “scholars of Edom”—i.e., Christendom—none of whom “dared to

contradict or malign” Scripture’s plain sense “despite their prodigious

investigations into the sciences.”

Abravanel

as critical biblical scholar

Abravanel

towed the line on many issues but he was outspoken on the matter of authorship

of certain biblical books. [See Kotzk

Blog: 347) ABRAVANEL’S HYPOTHESIS:] Around the time of Abravanel and

the Italian Renaissance, there emerged the phenomenon of the “Humanist

biblicists”, who had a sense of history and a critical reading of classical

and biblical texts. History and chronology became important. The Humanists attempted

to reconstruct a true account of the past from variant historical accounts. Issues

concerning biblical authorship never before explored, were now on the table and

open for discussion. According to Lawee:

“One of the only places to see signs of this development in Hebrew

biblical scholarship is in the biblical commentaries of Abarbanel.”

Abravanel

makes some interesting comments on biblical authorship with statements like

Jeremiah and Ezekiel being great prophets but deficient in their writing

ability. This is why there are some grammatical and structural irregularities

in the ketav and keri (the way the letters are sometimes written

and pronounced). Abravanel writes:

“I believe that Jeremiah was not very proficient in the ordering of

words or rhetorical embellishment, as was the prophet Isaiah and other prophets

as well. Hence, you will find in Jeremiah’s speeches many verses that all

commentators agree are missing a word or words…Similarly, you will find very,

very often . . . that ‘al [properly “on”] is used in place of ’el [properly

“to”], masculine for feminine and feminine for masculine… and the very same

utterance may switch from second to third person…” [Jeremiah,

297–98.]

He

continues to assert that Isaiah naturally spoke well as he was raised in court

and of royal descent, but Jeremiah was raised among village priests and

therefore expressed himself in less than perfect language (Lawee 2001:178).

While

Abravanel speaks of

some form of biblical editor (“metaken” and “mekabetz”) who

gathered various “documents” (“ketuvim” and “maamarim”), he

refused to apply these critical methods to the entire Torah of Moshe. (Lawee

2001:184) He did however question the provenance of the book of Deuteronomy

[See Kotzk

Blog: 342) HAYYUN’S HYPOTHESIS: DANCING BETWEEN THE LINES:]

Lawee

(2001:185) writes that one should not discount the possibility that Abravanel,

who wrote most of his Torah commentary towards the end of his life, may have

been expressing himself more conservatively than he might have in his younger

years.

Lawee

(2001:186) deals with the oftentimes conflicting poles of Abravanel’s ideology

by describing two different personas – Abravanel the exegete or commentator

and Abravanel the theologian:

“As an exegete shaped by some of the methods and mentality of

the Renaissance, Abarbanel could trace the textual history of biblical texts,

posit the unreliability of prebiblical scriptural sources, call attention to

linguistic and stylistic flaws in the speeches and writings of eminent

prophets, find witting bias built into a biblical book, and claim that an

author inspired by the Holy Spirit erred in his understanding of an earlier

biblical text.

As a theologian, however, and as a communal leader seeking to

reinforce belief in the rock-hard inerrancy of scriptural prophecies of

redemption, he was loath to admit that prophetic writings had ever experienced

“confusion,” and he insisted that the Torah in particular was immune to the

sorts of corruptions suffered by other texts handed down from antiquity.”

Abravanel’s

anti-midrashic stance

Despite

Abravanel sometimes leaning towards Christian faith-based interpretations, he

had an ambivalent attitude towards the overly creative Midrashim. Sometimes

he was prepared to “derive a bit of assistance from… the ways of the

midrashot” but other times he chose to “incline away from them”

(Lawee 2001:37).

Abravanel

did not escape censure for his approach to Midrashim. The kabbalist Eliyahu

Chaim of Genazzano condemned Abravanel who he referred to as the “man from

Portugal”[6], for defaming rabbis. He claimed Abravanel was trying to “destroy

the words of the rabbinic sages and all of the other commentators”. And

that Abravanel had:

“criticized midrash improperly—not in secret, quietly, and by

way of hint. Rather, he desecrated the name of the aggadists (ba‘alei ’aggadah)

in public.”

With

what Lawee describes as “a frequency and nonchalance uncharacteristic of

Rabbanite writers” Abravanel refers to Midrashim as “rachok”

(unlikely or far- fetched), ”very unlikely”, “insufficient”, “dubious” or “bilti

maspik”, “weak” and “zar” (foreign or strange).

Abravanel’s

anti-Rashi stance

Because

the great commentator Rashi quotes Midrashim in most of his commentary,

he did not escape the critical eye of Abravanel who writes:

“[It is] an evil and bitter thing” that “the great rabbi Rashi

contented himself in his commentaries on the Holy Scriptures in most matters

with that which the rabbinic sages expounded.”

Abravanel

also felt that Rashi had not dealt comprehensively with his commentary which

was written in “great brevity”. He questioned whether commentators like

Rashi knew that “the Torah has seventy faces” and that “the Holy

Scriptures contain ‘light and understanding and great wisdom’ [Dan. 5:14]”

(Lawee 2001:38).

Abravanel

went so far as to exclude Rashi from his call for diligent Torah study when he

saw that Ashkenazi Jews were neglecting Bible study and focussing only

on Talmud. (Lawee 2001:88) He generally had a rather dim view of

literalism in aggadic and midrashic interpretation and referred

to such simplistic readings as “the way of the Ashkenazim.” Included in

his view of even the most perfect of Ashkenazi sages, was the notion

that most of them were as “stammerers without understanding”[5] (Lawee

2001:44).

In

fact, Abravanel claimed to usurp Rashi as the commentator whose main purpose

was to explain “peshuto shel Mikra”, the plain meaning of the text of

the Torah (Lawee 2001:93). According to Abravanel, Rashi had lost this position

of expounder of the plain meaning of the Torah text because of his

preoccupation with Midrashim. That position was now held by Abravanel.

Abravanel

and Kabbalah

Abravanel

also had a complex attitude towards Kabbalah. He interpreted many kabbalistic

concepts neoplatonically. This meant

that in his view:

“certain ancient philosophic notions, ones advanced by Plato

especially, coincided with Kabbalah” (Lawee 2001:46).

He

maintains that a single universal truth pervaded the writings of “ancient theologians”

of the distant pagan past, and he believes that the kabbalistic sefirot

or spheres, were identical with Platonic ideas.

If

one needed more convincing on Abravanels’ approach to Kabbalah, this is

what he writes:

“I have no association with hidden things, and I have not traveled

the ways of the Kabbalah, for it is distant from me”;

“I have not studied the wisdom of the Kabbalah and the knowledge of

the holy ones I do not know” (Lawee 2001:131).

This

all seems to imply that for Abravanel, Kabbalah was not a “privileged

portion of authentic tradition handed down from antiquity” but instead something

“that Abarbanel might have mastered had he wished to do so” (Lawee 2001:47).

He did not choose to study Kabbalah because he questioned its authenticity

within the corpus of Jewish literature.

Abravanel

on Maimonides

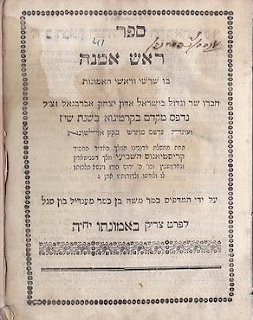

As

with so many other areas of Jewish theology, Abravanel entertained divided

sentiment when it came to Rambam. In his Rosh Amanah (Abravanel’s

Principles of Faith), he defends Maimonides’ Thirteen Principle of Faith

from the attacks of by the like of Chasdai Crescas and his student Yosef Albo.

Yet, strangely, he concludes that looking for principles of faith was misguided

in Judaism as “the entire Torah, and every single verse, word, and letter in

it is a principle and root that ought to be believed.” In other words, once

we have the Torah, we no longer need a further creed, which was rooted

anyway in non-Jewish perception of religion as dogma.

The

mixed messages Abravanel is sending is quickly reconciled when he explains that

principles of faith and compact dogma are necessary only for the masses who had

not yet “delved into the Torah” and needed simple heuristic devices

(Lawee 2001:49).

[Note:

A heuristic is defined as a mental shortcut that allows people to solve

problems and make judgments quickly and efficiently. Heuristics are helpful in

many situations, but they can also lead to cognitive biases.]

Abravanel

expresses his feelings on Maimonides and is recorded as saying after delivering

a lecture on Rambam’s Guide For the Perplexed in Lisbon:

“‘this is the intention of our master Moses [Maimonides], not

the intention of Moses our master.’” [Or ha-hayyim 96]

In this

instance, Abravanel is intimating that Rambam (Rabbeinu Moshe) had

broken with the tradition of Moses (Moshe Rabbeinu)! (Lawee 2001:32).

Abravanel

writes that he does not believe “all that the master [Maimonides] wrote”.

And “The good [in Maimonides] we accept and the

bad we do not.” He is prepared to praise Rambam for rebutting the

philosophers on three major issues, creation, divine knowledge, and providence

– but as for “the rest of the topics” there were in Maimonides “undoubtedly

things against which the traditionalist scholar (ha-torani) will protest” (Lawee

2001:56).

Analysis

It

emerges that Abravanel is not totally committed to rationalism or mysticism.

(Lawee 2001:46) Although Abarbanel’s leaning towards rationalism was far more

sustained and involved than his relationship with Kabbalah (Lawee 2001:208).

Similar

ambiguity exists, as we have seen, with trying to establish which persona is Abravanel’s

most dominant, Abravanel the commentator or Abravanel the theologian. Cedric Cohen-Skalli (2021:285) points out that "[i]n 1937, Yitzchak Baer made the point that

All

this makes it very difficult to place him in any particular “box”. There were

many other classical rabbis who are also difficult to categorise. This ambiguity

is most uncomfortable for us today, looking back on Jewish history through the

eyes of contemporary Judaism where allegiance to a particular approach or derech

is expected, required and sacrosanct. Today, the first question one gets asked

is “who is your Rov”? One wonders how Abravanel would have responded to such a

question and whether he would even have understood it.

[1] Lawee, E.,

2001, Isaac

Abarbanel’s Stance Toward Tradition: Defense, Dissent, and Dialogue, State

University of New York Press.

[2] Gershom

Scholem, “Revelation and Tradition as Religious Categories,” in The Messianic

Idea in Judaism and Other Essays on Jewish Spirituality (New York: Schocken,

1971), 290.

[3] Leo Strauss, “The Mutual Influence of Theology and Philosophy,” The Independent Journal of Philosophy 3 (1979): 112. (p.6)

[4] Parenthesis

mine.

[5] She’elot…Sha’ul

ha-Kohen 6v.

[6] Don Isaac’s seventy-one-year-long life can be divided geographically into three periods: the Portugal phase (1437–83), the Castile phase (1483–92), and the Italy phase (1492–1508). (Don Isaac Abravanel: An Intellectual Biography, Cedric Cohen-Skalli, Translated by Avi Kallenbach, 2021, vii.)

[7] "Unlike the classical Jewish exegetes Rashi, Ibn Ezra, and Radak, who commented on single verses and even on single words, Abravanel contends with full “units”—that is, broader literary units defined and demarcated by the principle of a single “story” or idea. This method of homiletical exegesis has major similarities with certain fourteenth- and fifteenth-century homiletical works such as those of Rabbi Nissim Gerondi (HaRan, c. 1300–c. 1376) and Rabbi Isaac Arama (c. 1420–c. 1494, author of ‘Aqedat Yitshaq). Interestingly, Abravanel portrays his choice as a golden mean between the methods of Gersonides and the translation and commentary of Jerome" (Cohen-Skalli 2021 :113).

[8] "Don Isaac depicts the Christian “scholars” as intellectuals who, despite their profound knowledge of philosophy and science, do not cast any doubt on creation ex nihilo or the possibility of miracles. Abravanel admires their ability to separate religion from philosophy and science, as well as their success in finding a golden mean between the two camps" (Cohen-Skali 2021:126).

No comments:

Post a Comment